Reconciliation Over the Graves? A German War Cemetery in Russia (or the German-Russian Reconciliation of Sologubovka)

Nina Janz

University of Hamburg

Nina Janz was a Harry & Helen Gray/AICGS Reconciliation Fellow in 2016. While at AICGS, she will investigate the historical dialogue and the peacemaking process between Germany and Russia seventy years after World War II. Under the slogan “Reconciliation over the Graves” the German War Graves Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V.) still tries to exhume and bury soldier’s remains, builds war cemeteries and commemorates the war dead. Based on a case study, a German war cemetery in Sologubovka (St. Petersburg), she will examine the approach between the former enemies, between the defeated and the victors. Despite the invincible gap between two national memory narratives, the German war cemetery should symbolize reconciliation and understanding towards the Russians. At AICGS Nina Janz investigates the efforts and the process of reconciliation “over the graves” of the war dead in Germany and Russia today.

Nina Janz is a PhD candidate at the institute of cultural anthropology at the University of Hamburg, focusing on culture historical case studies on soldiers’ death and the hero cult during World War II. She worked for the German War Graves Commission in Berlin and participates in the international youth work for German and Eastern European teenagers in history and memory projects on topics like World War II and the Holocaust.

The remains of millions of soldiers still lie in the soil of the former battlefields of World War II in Europe. Since the end of the war, Red Army and Wehrmacht soldiers’ remains have been (and continue to be) recovered by Russian and German teams in Kursk, Smolensk, Volgograd (Stalingrad), and St. Petersburg (Leningrad). The dead are exhumed, identified, and reburied in war cemeteries.[1] One of the war cemeteries is Sologubovka in northern Russia, around 70 km from St. Petersburg.[2] There, 54,247 German soldiers[3] lie on 5 hectares, with space for 80,000 graves,[4] taken care of by the German War Graves Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V.).[5]

The German war cemetery on Russian territory is not a simple resting place. The dead attacked the Soviet Union, occupied the region of former Leningrad, starved over one million civilians to death, and left the land with violence, suffering, and pain. Fifty-five years later, in 2000, German official delegations, journalists, and the families of the dead arrived in the village of Sologubovka to memorialize the inauguration of the German war cemetery. The way was paved by signing a war grave agreement between Germany and Russia in 1992. Does the construction of a cemetery by the Volksbund for the former defeated (Besiegter), in the country of the defenders, such as Russia, signify an approach to an understanding between the former enemies? Is reconciliation possible if one country celebrates the victory and the defeated country mourns? Does the respect shown in the humanitarian and dignified treatment of the dead (also of the former “enemy” dead) symbolize a historical dialogue between Russia and Germany?

“Reconciliation over the graves”[6] is the official slogan of the Volksbund, a non-government organization based in Kassel, in central Germany. The Volksbund builds resting places for German war dead, and commemorates and acts in educational youth work toward understanding and harmonization after World War II. This essay uses and follows the definition of reconciliation as intended in the meaning of the Volksbund’s activities in Russia. The idea of this slogan and the purpose of this term will be explained. Based on the German war cemetery in Sologubovka, this essay focus on the cooperation between Russians and Germans—the Volksbund, the local population, and the authorities—on the treatment of the war dead, on the different national historical memories, and on the approach of two countries more than fifty years after World War II.[7]

The Russian General Alexander Suvovov said in 1799, after beating Napoleon in Italy: “War is only over when the last soldier is buried.”[8] So will World War II finally be over when the last soldier of the over 20 million fallen[9] will have been found and buried properly? Will the reconciliation then be successful, when all dead are buried?

From Heroes and Victims: The Politics of War Dead in Russia[10] and Germany

“Nobody is forgotten, nothing is forgotten.”[11] The Soviet/Russian[12] remembrance slogan shows the will and the necessity of remembrance. Russia did not forget and so it remembers, commemorates, and celebrates its victory over Nazi Germany. Approximately 20 million soldiers and civilians died in battles or were killed, murdered, deported, and abused by the German police and Wehrmacht on the former territory of the Soviet Union. The “Great Patriotic War,”[13] as World War II is called in Russia and other former Soviet states, accompanies the people in every city and town today in the Russian Federation. The memorials, museums, cemeteries, and victory parks announce and publicize the glorious victory over fascism. On May 9, Victory Day, the successful suppression of Nazi Germany’s aggression is celebrated and the glorious defenders of the Motherland were and are honored and adored. The Soviet Union celebrated itself and the survival of the socialist idea, in which the Great Patriotic War became an important part of Soviet ideology and propaganda for self-confirmation und self-empowerment.

The Soviet and Russian memory narratives of World War II knew only heroes. The mythology and inflated legends of the protection of Mother Russia served as a symbol for Soviet identification.[14] Although memory under the different decades—Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev and Yeltsin—differs, the message (especially after 1965) continued after the end of the Soviet Union and the foundation of the national states, such as Russia. During Gorbachev’s glasnost and especially after the end of the USSR, critical voices rose against the official version of the war. Nevertheless, the parades on May 9, Dyen Pobedy (Victory Day), are just as powerful in Putin’s presence and are similar to the parades in the 1960s and 1980s, in the bloom of the Soviet Union.[15] The contemporary Russian official narrative is just slightly modified from Soviet times, but the traumatic experience has not been worked through and reflected on, and grief work has not been undertaken.[16] So on Victory Day, on May 9, the heroes of the successful defense of the Motherland are still celebrated in the parade on Red Square.

The country of the defeated has no comparable parades. Germany was defeated and confronted with its crimes and guilt. The country was occupied, divided into two states and two ideologies. A collective memory or mourning without a common representation was not possible. Memory of the past became a family affair.[17] The dead were mourned but without asking about the reason for their death.[18] German grief did not focus on the Jews killed in the crematoria; the Germans mourned their own losses, such as the people who died in the Allied bombing raids and during the deportations from the East, and the five million fallen soldiers.[19] Germans converted their private and personal tragedy into a national tragedy.[20] German people could not explain or justify the war and the violence, but they mourned. Postwar society did not differentiate between the losses. The dead became victims: the bombing dead, the refugees, the murdered, and the soldiers were called victims. In Germany, the notion of a “collective victim” grew. [21] Hitler’s Volksgemeinschaft (national community) was replaced by the Opfergemeinschaft (victim community) in the postwar period and the beginning of the Federal Republic of Germany.[22] In German the word Opfer means victim and sacrifice. The meaning of the word changed: From the National Socialist meaning “sacrifice” as the active object into “victim,” the passive object. The war memory in Germany was victimized. The awareness of their own suffering concluded a defense of their own guilt.[23]

The soldiers became victims as the Germans of the 1950s, 1960s, and even until the 1990s, switched the private tragedy (the death of the father, the loss of house, or flight, hunger, uncertain future) into a universal or national tragedy.[24] The focus of the national memory was on the fallen soldiers. The largest group of Germans served in the Wehrmacht (ca. 18 millions)[25] and were the largest group of war dead—five million German soldiers died or were missing in action, while “just” 400,000 civilians died during the war.[26] Responsibility was partially accepted by German society, but the blame was put on Hitler and his elites, like the SS. The Wehrmacht was long regarded as “clean,” and thus innocent.[27] As the war generations died, and after the famous Wehrmacht exhibition of the Sozialinstitut für Zeitgeschichte in Hamburg (1995-1999), the Wehrmacht’s crimes on the Eastern front became public knowledge, despite being already accepted as a fact by historians. After the shock and the protests by veterans,[28] the crimes and the German responsibility for the victims of National Socialism and their suffering were recognized, although some groups, such as the Soviet Prisoners of War, are still fighting for compensation.[29] The German Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit (confrontation with the past) is still in process; from ministries to companies, the past in the Third Reich has still to be fully unraveled.

These two versions of one war—the Russian and the German—show the difference in the narratives of World War II. The national memories of Russia and Germany could be called a hero’s narrative (Russia) and a victim’s narrative (Germany). These two different messages and interpretations collided on the soil of Sologubovka.

The War Dead and Their Graves in Germany and Russia

In this essay, German-Russian reconciliation efforts are measured by war graves. To quote Charles de Gaulle, “The culture of a people can be recognized in how it treats its dead” and to complete the sentence: and how it treats the enemy dead. World War II cost more than 55 million people their lives. If for every war dead a single grave was built, the whole of Europe would be a cemetery.

The message that war cemeteries can send are clear: death and human extinction. Somebody who has visited a war cemetery, with 30,000 or 50,000 crosses stretching to the horizon, understands the overwhelming feeling. The names of the dead—women, men, and children—and their life dates (mostly young people) reinforces the senselessness.

The Volksbund’s projects under the title “reconciliation over the graves” take the resting places as the foundation for its practice and cooperation with Russia. Why the war graves? Why not focus on the living? Burial grounds are attached value in every postwar country. Every former war side, no matter if culprit or mourner, suffered a death toll. The slogan “over the graves” allows a communality for the former opponents and the human will to bury the dead and to commemorate them.

The Significance of War Graves[30]

Burial grounds were first constructed due to the urgent need to bury the dead, both for ethical and hygienic reasons. There is also a cultural aspect: the dead hold a place in our individual memory. The burial ground becomes a site of memory, from religious, political, ideological, and personal aspects. The significance of the resting places of the war dead is visible in the categorization of war graves in the Versailles Treaty and the Geneva Conventions. After World War II, the Geneva Convention protected the graves of soldiers and of the civilians killed during the war; this convention was renewed in 1949. The signatories in Europe were obliged to take care of the graves on their territory, including the enemy’s graves. Countries of the former German occupation concluded a special agreement with Germany concerning the preservation and protection of the German graves abroad; the first was signed in 1954 with France.[31] In Western Europe, the Volksbund started to search for the missing, to register the graves of the fallen, and to notify the families as early as 1946. Access to graves in countries behind the Iron Curtain was not possible.[32]

In Germany itself, a special law for war graves was enacted in 1952. It served to protect the resting places of Nazi victims, meaning Jewish concentration camp prisoners, political opponents, forced laborers, and soldiers.[33] These graves and these groups were interpreted as “war dead.” The general expression was and still is “Victims of War and Violence.” That means not only the German soldiers, but also the fallen SS and police—thus, perpetrators, supporters, or participants of the German crimes were included in this expression. The dead of the crematoria, who lost their lives through forced labor, deportation, and exploitation, were equalized with the soldiers.[34] This equal treatment of the war dead shows the so-called “victim’s memory,” which is typical for the German postwar society, and represents the message: Death is no respecter of persons.[35] No differences had been made.

The grief concerning the losses allowed the graves to become a symbol: A symbol as a reminder for peace, a reminder for understanding, a reminder for the future and the next generations.[36]

German-Russian Cooperation on the War Graves

Since the 1950s, the Volksbund tried time and time again to obtain access to the burial grounds, but without success.[37] A Soviet diplomat stated that no German graves would exist on the territory of the Soviet Union, but in 1988 the first cemetery visit for families of German dead POWs occurred, meaning “one door is open.”[38] The Volksbund’s youth work, in which teenagers and young people engage in grave maintenance and commemoration of the war dead, also supported the approach between the two countries: In 1988 and 1989 young people from the Soviet Union took part in a Volksbund youth camp in Germany.[39] The door was opened further after unification, when unified Germany signed the Good Neighborhood, Partnership and Cooperation agreement with the Gorbachev government on 9 November 1990. The agreement contained details not only about renouncing violence, disarmament, and the recognition of borders, but also about the legal protection of the Soviet memorials in Germany.[40] The next step was the war grave agreement, signed on 16 December 1992 in Moscow and entered into force on 6 May 1994.[41] This declaration was “led by the desire, to grant the war dead of both sides a dignified last resting place,[42] aware that the maintenance of the graves of the war dead on German and Russian soil constitutes a concrete expression of the understanding and reconciliation between the German people and the peoples of the Russian Federation.”[43] The war grave agreement recognizes the war dead and the human losses on both sides at the international level, a novelty in relations between Germany and Russia. In the same year, the first Volksbund delegation visited a former World War II battlefield in Volgograd, and laid the first stone for the German cemetery, and the work began.[44]

Today, the Volksbund supervises five large collective cemeteries in Russia, and since 1993 the staff has exhumed and reburied 380,000 dead. The relationship with Russian authorities, in exhumation and construction of the sites, is positive and successful, and when problems arise they are often overcome by a reminder of the interstate agreement and the existence of Soviet war graves in Germany.

War cemeteries managed by the Volksbund offer history and war facts, announce the loss of civilians, and consider the pain and suffering of the locals, but they are not supported everywhere. There are cases of grave robbery, and criticism from veterans, authorities, and locals. For them, the Volksbund does not distinguish between victims and perpetrators. The Volksbund advances the view that every death is equal, no difference is made, and accents the humanitarian aspect of its work.[45] It operates under guidelines to recognize German responsibility and guilt and to remember the war dead, without honoring them. This sounds simple, but includes many controversial discussions, mostly from inside the organization.[46]

German-Russian Joint Commemoration Projects

The war grave agreement from 1992 addresses not only the German graves in Russia, but also the Soviet/Russian war graves in Germany, of which there are over 350 bigger and smaller cemeteries, mostly in eastern Germany.[47] People from the Soviet Union who died during battles (soldiers), exploitation, due to hunger and illness (slave laborers), or prisoners in concentration camps (POWs, Jews, and other persecuted ethnic people) are buried in Germany. These graves are categorized as war graves and fall under the national German law from 1952 and the German-Russian war grave agreement. Although these graves are protected and their existence ensured, there are also critical voices who see the Soviet graves and memorials (such as the famous memorials in Tiergarten and Treptower Park in Berlin) as part of the hero’s cult of the Great Patriotic War in Germany, with its splendid cemeteries, obelisks, and sculptures.[48] Different than in Russia itself, the graves of the so-called forgotten people in Russian national narratives, such as forced laborers and POWs, find a place in the German memory landscape.[49] In Russia private initiatives since the 1990s have shown interest in these war dead and victims and try to include these groups in the national memory.[50]

There are initiatives and efforts for a joint commemoration of World War II in both countries, from historical commissions, to joint forums, youth work, and textbook projects.[51] But there are still disagreements over dealing with the past. An example is one of the latest events: the celebrations for the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and Germany’s surrender. Russian president Vladimir Putin invited state leaders and German chancellor Angela Merkel to attend the military parade at Red Square. Most of the invitations were rejected, and Merkel was the only western European leader to travel to Moscow to commemorate the end of the war. She declined the invitation to attend the military parade in Red Square, but she arrived one day later and laid a wreath at the grave of the Unknown Soldier.[52] Although present-day politics have cooled relations between the two countries, in commemoration, neither wants to come in second.

Sologubovka: A German War Cemetery in Russia

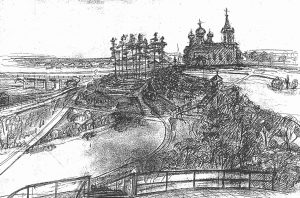

In the village of Sologubovka, behind the river Neva and the Soviet memorial places Sinyavino Heights and Nevski Bridgehead, rest soldiers of the German Wehrmacht, who died in World War II in the siege of Leningrad.[53] The old Russian Orthodox church in the village was used during the war by the Wehrmacht as a hospital; the fatalities were buried next to the church. The cemetery contained over 3,000 soldiers during the war, buried in single graves with their names marked on crosses. By 1994, the cemetery was overbuilt, the name marks removed, and the graves barely visible. After the German-Russian war grave agreement, the Volksbund began its search for the fallen and missing soldiers and started the investigation in the region of Leningrad for a suitable site for a larger cemetery. The village of Sologubovka offered enough space and the proximity to infrastructure for future visitors, and the former German military cemetery by the church marked the starting point to bury additional remains.

The construction of the site, designed by a Russian architect and the Volksbund, and the reburying of exhumed Germans[54] started right after 1996 and cost DM 1.9 million.[55] Today the soldiers lie in single graves, covered by a lawn a few symbolic crosses stand scattered in couples. A simple grey cross marks the center of the cemetery, and grey granite steles on the main walk stand beside the road with the names of the buried soldiers.[56]

Every plan and design was supervised by the regional authorities in Kirovsk. Before even burying the first soldier, soil and water samples, measurements, markings, plans, and designs had be approved by the regional authorities, with the Russian partners in Moscow and the Volksbund in Germany, and even taking into account the views of the Orthodox Church, veterans organizations, the local population, and the media. After almost five years, the complex was inaugurated in 2000.

“Germans, finally. I have waited for them for 56 years!”[57]

Reactions, Protests, and Support from the Russian Side

But before the cemetery could be opened for the public, the largest protest group, the veteran organization in St. Petersburg, had to be convinced. The former soldiers expressed opposition toward this project and some of them protested against a German cemetery on Russian territory.[58] To win the veterans’ support was an important condition on Volksbund’s agenda. How to do so, after they experienced death and violence at Germany’s hand during the war, remained a question. The Volksbund appealed to the veterans on a human level and invited them to visit the graves of their comrades in Germany and to see with their own eyes how they are cared for. In the spring of 2000 a group of veterans from St. Petersburg commemorated their soldiers in Germany. This visit is described by many Volksbund staff as the turning point in the veterans’ support for the German war cemetery in Sologubovka.

The German War or When the War Started

The difficulties and the collision between the two sides began at the entrance to the cemetery. The Volksbund planned to engrave the stone and the plaque at the entrance of the complex as it had on burial grounds in France, Italy, and the Netherlands: Deutscher Soldatenfriedhof (German Soldier Cemetery), the location of the cemetery, and the years 1939-1945. The Germans used the year of 1939 to mark the beginning of the violent conflict. The Russians preferred using the year of 1941, the start of the attack by the Nazis and the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, the defense of the Motherland.

The start and end date of World War II marks the time period in which German soldiers died. But for Russian authorities, the war did not start in September 1939, but in summer 1941. The Russians pointed out that the war started in the region of Leningrad in 1941 and ended in 1944. The soldiers who died during these battles did so during this period. The Volksbund saw in the 1939-1945 dates a broader perspective, and the classification of the siege of Leningrad in a wider context. The Russian perspective puts the emphasis on the region, and does not see the war as a global war, but rather as their war, a unique, special case for suffering and heroism. The Russian veterans did not connect the violence in Leningrad with other parts of the world, while the Germans do not distinguish war regions, countries, periods, nationalities, and ethnicities. But for the Nazis there were differences in ideologies and nationalities. The war in France has to be distinguished from the extinction in the Soviet Union. The Volksbund could not succeed and the dates of the Great Patriotic War in Leningrad were engraved. The Great Patriotic War did not end in 1944, but in 1945—and so the five was turned into a four, to emphasize the war in Leningrad.

Already the entrance of this burial ground shows the difference between two national war narratives, histories, and interpretations, in which the German Volksbund was confronted in Russia by the history of victims and heroes, depending on the side with which the reader identifies.

The inscription at the center of the cemetery was also part of an argument. The originally-intended inscription was “In Memory of German soldiers, who fell in World War II and who are buried in this cemetery.” But the Russian veterans asked the Volksbund[59] to change the inscription to: “In Memory of the soldiers, who fell ….” The additional German was erased from the stone, implying a neutral meaning of dead soldiers. The cemetery was thereby denationalized and generalized. According to this inscription these soldiers did not die for Hitler or Nazi Germany. At first glance, this makes sense. The soldiers in the Wehrmacht were not only from Germany, but also from Austria, Italy (South Tirol), and Alsace, and Volunteers from Flanders, so Belgian, Dutch, and Danish. So the name of “German Soldier Cemetery” is not representative.[60] But this inscription puts the dead into a neutral context; it does not say anything about the purpose or the war history. This seems like a humanization of every soldier’s death, within the meaning of the Volksbund’s memory practice.

But the original intention should be interpreted differently. The Russian veterans requested to erase the German addition, whether to disconnect the soldiers from their nationality and army or to avoid national memorials for the Nazi aggressors. This shows the deep fear of and hatred toward the Nazis and with all things German that are connected to the war.

The only hint that the Sologubovka site is a German cemetery is the plaque at the entrance to the complex.

The “Church of Reconciliation”

The highest point and the dominant part of the cemetery complex is the Russian Orthodox Assumption of Mary church. The church was built in 1851, looted in the 1920s, and closed in 1937 after the priest was arrested and murdered by the Stalinists. During World War II, the German Wehrmacht occupied the little village of Sologubovka, used the church as a hospital, and buried their dead nearby. The church remained undestroyed during the war; the Wehrmacht only removed the church’s tower in self-defense, because the height of the tower served as an easy target for the Soviet artillery.[61] After the war, the church fell into disrepair and was used as a cinema and as a storage room. The Orthodox community continued to use the undestroyed parts of the church for worship. In exchange for receiving the territory in Sologubovka, the Volksbund agreed to rebuild the church. The territory was not in use by anyone—it was marshy and undeveloped—and before the Volksbund could start to bury the soldiers, a road had to be constructed that would connect the main road in the village to the cemetery, and so also to the church.

At first, the German side was unwilling to rebuild the church. In their opinion, the Wehrmacht had not destroyed the church in the war, so it was not Germany’s fault that the building was crumbling. In initial designs, the church was not included in the complex. In fact, the Volksbund’s original idea was to preserve the church as a ruin as a reminder of war, like the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin.[62] The main reason for this could have been the cost of the renovation.[63] After letters and protests from the Kirovsk region, the church, and the veterans’ organization in St. Petersburg, and after internal discussions in Kassel, the Volksbund decided to include the church in the slogan “reconciliation over the graves” and to name it the “Church of Reconciliation: Construction for the Future.”[64] The reconstruction was financed by the Volksbund and by donations. The icons in the new church were painted by a German veteran and today decorate the altar. In 2003, the church was handed over to the Russian Orthodox community.

The reconstruction of the church was a necessary and important step in the dialogue with the Russian partners. The renovation led the Russian side—including the church’s priest, Father Vyatsheslav—to finally support the Volksbund and its intentions. He persisted and pushed the Volksbund to its decision to rebuild the church, but he promoted as well the idea of the church of reconciliation and the Peace Park (described below). He was an important actor in convincing the Russian partners—especially the veterans.

The combination of the cemetery and the Orthodox church corroborates the message of the Peace Park and reconciliation. The complex was built with a Christian perspective, with cemetery and church on the territory. This message met with approval from the Russian partners. The process was one of give and take: The Volksbund rebuilt the church, the Russians supported the cemetery—an ideal compromise. Even the church itself is used by both sides. The Russian Orthodox community in Sologubovka celebrates its worship services in the main hall of the church, and downstairs, in the former catacombs of the Wehrmacht’s hospital, the Volksbund has an exhibit on its work, a room of remembrance for families of the soldiers, and books with names of all missing German soldiers (on Russian territories). Russians and Germans are under one roof.[65]

A Memorial for the “Fascists”? The Sculpture of the Mourning Mother of Nagasaki

The biggest disagreement between the Russians and the Volksbund was over a sculpture by German artist Yrsa von Leistner, who donated her sculpture Mourning Mother of Nagasaki to the Volksbund in 1994 for an installation at the war cemetery in Sologubovka.[66] The cemetery designers planned to install the sculpture in the center of the cemetery, but this evoked the biggest protests from Russian partners, who preferred the installation of a simple cross instead of the Mourning Mother. The Volksbund identified the sculpture as mourning parents, who lost their sons in the war. In their opinion, the sculpture shows the effects of war and violence and stand as a reminder for future generations. The Volksbund sees the sculpture as a gift and a gesture for peace, from a German artist to the Russian people. Copies of this figure stand in Nagasaki and in the U.S. This symbol of the friendship between Germany and Japan and Germany and the U.S. should therefore be transferred to the German-Russian case as part of the Volksbund’s message of reminding and warning.

The Russians interpreted the sculpture differently. The installation of the Mourning Mother would categorize the German soldiers as victims and elevate them to innocent objects of war, or even more, equate them with the victims of the siege of Leningrad. Many protest letters and articles reached the Volksbund in Kassel. The installation of this sculpture would monumentalize the cemetery, according to Russian opinion, and would place the soldiers and their actions on a pedestal to be remembered and admired. Even the name “Nagasaki” connects the helpless victims of the U.S. nuclear attack on the Japanese city of Nagasaki with the innocent victimhood of the German soldiers. Russian partners demonstrated vehemently against the sculpture and all it implied. A 1997 letter from the Center of Reconciliation in St. Petersburg reminded the Volksbund to design the cemetery as a “modest” complex and warned the Volksbund that the figure would “damage the reconciliation processes between the people.”[67] Furthermore, the sculpture stands in Russian eyes as a “Memorial for the Heroes of the Fascism.”[68] “No, dear gentlemen,” wrote Andrej Wermischew in 1997, “this is not some soldier cemetery. It is [a] German soldier cemetery in RUSSIA.”[69] The church, the city of St. Petersburg, and the veterans pushed the Volksbund to install a cross instead of the sculpture.[70] The German Consul General in St. Petersburg intervened in this standoff and asked the Volksbund to remove or relocate the Mourning Mother. In the end, the partners found a compromise: the Mourning Mother of Nagasaki was installed beside the cemetery in the Peace Park, close to the church, and was dedicated to all victims of the war. A simple grey cross now stands in the center of the cemetery.

German “Designer Cemeteries” vs. Russian Mass Graves

The harshest responses were triggered by the decision to construct this cemetery in Sologubovka.

While the remains of the Red Army soldiers are buried mostly in mass graves or were anonymously exhumed,[71] almost every Wehrmacht soldier can be identified.[72] This generated dissatisfaction and envy in the Russian families who lost a family member in the war. Many complained about the lack of understanding inherent in building cemeteries and monuments for “occupiers and fascists” in “designer cemeteries”[73] and the shame of not providing the same for their own dead. A poll in 2007 by the radio station Echo Moskvu shows the variety of expressions concerning German cemeteries in Russia, from the war graves as “propaganda of fascism” to convictions that the “dead have to be buried.”[74] Russian veterans see the work of the Volksbund with envy and respect.[75] One Russian woman said in a 2000 interview: “Some think it is shame, that the victors must help the vanquished to bury their dead.”[76] Others blame the authorities for not taking care of their own graves, like Andrej Wassijellew: “Rather than building dignified graves for the Fatherland defenders, the Soviet state constructed grandiose, but anonymous, hero’s memorials.”[77]

One local elderly resident of the village of Sologubovka waited for fifty-six years for the return of the Germans.[78] Lida Titarenko, who was enslaved by the Wehrmacht during the occupation, claims “The Germans destroyed this place. Now they’re rebuilding it. That’s good!”[79]

The opinions vary from absolute opposition to support. The positive effects were pointed out as well: the construction of the road, the renovation of the church, jobs in gardening and construction for the locals, as well as an influx of tourists and the families. The Bavarian Red Cross invested in a children’s facility in Kirovsk, close to the village,[80] and the Volksbund renewed some memorials and graves for Soviet soldiers.[81] But it appears that the Germans paid the authorities and the organizations for the war cemetery. In the words of Zoya Kornilyeva, deputy head of the World War II veterans in St. Petersburg, “The Germans are always preaching reconciliation, but we’re not prepared for that. They go around paying big money and unfortunately our people fall for that.”[82] The belief that the war cemetery in Sologubovka was bought is a serious prejudice and burdens the relationship with the German Volksbund. The accusation remains unresolved and shows the variable efforts between the two partners, between refusal and support.

Ways of Reconciliation, Ways of Dialogue in Sologubovka

The previous section discussed problems, reactions, and the practice with war graves in Russia. But how do we define the work of the Volksbund in Sologubovka as an aspect of reconciliation?

From the beginning, the Volksbund tried to establish the war graves as an expression of reconciliation, understanding, and peace between the two countries. The cemetery is embedded into the whole memorial complex, which contains a Peace Park as “a symbol for the growth of peace between the people” and the restoration of the Russian Orthodox Assumption of Mary church as a “reconciliatory gesture.”[83] The Peace Park is connected with the cemetery; winding paths were constructed around trees, donated from sponsors worldwide.[84]

The efforts of the German War Graves Commission were accompanied by difficulties, compromises, and support of its intentions. The Volksbund tried to satisfy the Russian partners as much as possible: they built the road, reconstructed the church, renovated the Soviet graves, donated to children’s services, and invited the Russian veterans to visit cemeteries in Germany. The Volksbund reached out to the Russians.

Difficulties

The difficulties in the German-Russian reconciliation process can be described as deferred contact, inequality of the actors, the constraints of the German-Russian war graves agreement, and the issue of forgiveness. Due to geography and political events,[85] Germany and Russia could not act, exchange, or cooperate together until the 1990s. Almost fifty years after the war, the veterans, states, and NGOs like the Volksbund could address those situations that were addressed with France in the 1950s—forty years earlier. By the time the planning process for Sologubovka began, most of the Russian veterans were no longer in charge; the second generation was responsible in the local regional authorities. They experienced the stories of their parents or suffered the loss of a father, and were, of course, influenced by the strong war narrative from the 1960s and 1970s during the Brezhnev era. It was not easier to deal with this generation, but personal hatred and prejudice was not the biggest obstacles. The challenge is still the general dealing with the war’s memory, and the pride-driven (Russia) versus the grief-driven (Germany) narratives.

The whole process in the case of Sologubovka shows the glaring disparity and asymmetrical relationship between the actors. In Sologubovka, those actors were the regional state authorities and the church, who negotiated with the Volksbund, a non-profit organization. The cooperation between the two countries worked on different levels. Germany came as a penitent and as petitioner. Even the cemetery’s 2000 inauguration ceremony showed the uneven importance of the graves in both countries: the participants from the German side were high-ranking politicians like the mayor of Hamburg (the sister city to St. Petersburg), Bishop Maria Jepsen of the German Lutheran diocese in Hamburg, and the Volksbund delegation.[86] The Russian guests attending the ceremony were mostly locals, including from the metropolitan area of St. Petersburg, but no politicians from the actual city of St. Petersburg or the region came to the ceremony. The discrepancy between the condition of the German and Russian graves also highlights this inequality. The Soviet graves in Germany were taken care of, preserved, and financed by German authorities, while the German graves in Russia were unprotected until 1992 and, for those that were not irredeemably lost, have to be restored and built with German money. Russian and German interest in reconciliation can be measured by the treatment of these resting places, by the different categorization of the war dead in Russia, and by the Russian opinion that Germans do not deserve memorials or single graves.

The signing of the war graves agreement at the highest level was an important step for both countries and their relationship. But the signing of a document did not automatically lead to an open dialogue and a way of understanding. The content of this agreement seemed not to be valid in every district in Russia. The Volksbund staff had to deal with inconvincible governors during negotiations about exhumations and construction permits. The representatives of the Oblasts seemed not to know or to be unwilling to know or follow the instructions and the content of the war graves agreement decided in the distant Moscow. The Volksbund sometimes had to ask the government in Moscow to mediate and convince the local authorities.[87] Cooperation on the issue of war graves has to be imposed by the state in order to make the effort to engage in a dialogue with the descendants of the war dead.

The most controversial and difficult aspect is the question of forgiveness. “I ask for forgiveness for the cruel crimes of the German people,”[88] wrote a German visitor in the church’s guest book. The Germans sought access to their war dead and to start a dialogue with their former enemy, with the overall goal of achieving forgiveness between each other. But the process is handicapped by the Russian memory saying that “nothing is forgotten, nobody is forgotten.” For the Russians, it is one thing to give the Germans territory to bury their dead and another thing to forgive the crimes. For some locals, the war dead are still Nazis and fascists and will remain so. But the fact that the Russian partners allowed the cemetery in Sologubovka to be built is a way to pardon the war dead, or to accept them. But the step of actual forgiveness will never be fulfilled.

Achievements

The achievements and successful steps in the process of reconciliation is inherent in the following factors: signing the German-Russian war grave agreement; the Volksbund as protagonist and achiever; the slogan “reconciliation over the graves”; and practice and projects, such as youth work and commemoration.

The German-Russian war grave agreement from 1992 (and earlier the Good Neighbor agreement of 1990) built the base for further work on cemeteries in both countries, legally and politically. Within its framework, the Volksbund is has permission to exhume and to construct cemeteries on Russian soil. At the same time, the Russian graves are preserved and accessible on German territory. The agreement guarantees the eternal right for the war dead to rest in their graves, which is maybe the most important achievement between Germany and Russia and within the recognition for its war dead.

The Volksbund also feels responsible for remembrance of the war’s casualties. Based on this duty, the graves do not symbolize only the last resting place for the dead, but rather the meaning of these places changed. This attitude helped achieve cooperation and negotiation with the Russian partners. Because the Volksbund is a private organization, dependent on donations, it is able to achieve more than could officials from the German consulate.

Since 1919, the Volksbund’s logo has been an image of five crosses. The need to bury the dead, to mourn, and to remember are not only Christian needs, but are human needs. The idea of “reconciliation” and extending this idea to the organization’s slogan came from a Jesuit priest, Theobald Rieth, and his organization The Initiative Christians for Europe.[89] In 1951, he began a work camp at war cemeteries with the slogan “Reconciliation over the Graves” and developed the basis of European youth work.[90] He and 430 participants from over thirteen countries worked together on the Belgian war cemetery in Lommel, gardening and constructing new parts of the complex. The Volksbund adopted this slogan and continued working under this message.[91]

The Volksbund’s attitude toward forgiveness received many negative reactions in Russia. For the Russians, the crimes committed by the Germans could never be forgiven. But under the principle that all people deserve to be buried, the Volksbund could achieve the building of the war cemetery in Sologubovka.

The idea[92] to see graves as preachers of peace[93] supported the educational and youth projects. The peace education[94] and the slogan combined with the youth camps “Work for Peace” is still a guideline for the camps today. The starting point for the work camps was the exchange in Lommel in 1951. Every year in Western Europe and Germany, so-called work camps were organized and teenagers from all over Europe worked together in the preservation of war cemeteries and memorials. Due to the Berlin Wall, young people from Eastern Europe did not take part, until 1988. In that year and the following, teenagers from the Soviet Union participated in a Volksbund work camp in Herleshausen, Germany, and cared for the graves of Soviet POWs. One teenager, Katja, said during that time: “it is good to take care of the Soviet graves for the first time, because it is first step to avoid wars.”[95] Since the 1990s, work camps are organized as well in Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. In Sologubovka, the first took place in 1999, before the official inauguration of the complex. The youth exchange between German and local teenagers got many positive echoes in the region and the media.[96] Nearly every year young people from both countries meet in Sologubovka. The organizers focus on cultural exchange, as well as on historical-political education topics like human rights, democracy, and anti-racism. The work on the cemeteries tries to help the young people to value peace and freedom, like no history lesson can provide. The camps activate the awareness of these Europeans against extremist ideas, show them to respect the dignity of every human, and teach them responsibility for their deeds.[97]

The Volksbund’s youth program already received positive recognition at home and abroad. The organization won prizes like the Westphalia Peace Prize[98] in 2014 and gold medal of the Luxemburg Foundation du Mérite Européen. According to the prize organizers, the Volksbund builds bridges of friendship between former war enemies.[99] Since the 1950s almost half a million people have taken part in the projects of the Volksbund.[100] The projects are mostly co-financed by the German Federal Ministry of Family and Youth and by youth exchange foundations, such as the Stiftung Deutsch-Russischer Jugendaustausch or Russian regional partners.

Despite the idealistic aims of these youth camps, difficulties are still encountered, starting with funding (mostly the Russian partners could not find enough resources) and the different understanding of the war history as determined by national narratives, family histories, and textbooks. The projects should try to accept the differences and to find communalities. The Volksbund’s method is to work with biographies of the soldiers and to break down war history to the level of personal stories of the men and woman of that time. The idea is to humanize and to focus on the individual, detached from one’s membership in the Wehrmacht, SS, or Red Army. However, the danger is to equalize victims and perpetrators (not based on nationalities), and not to differentiate between the acts and decisions of these people.

The Volksbund evokes critical voices about this humanization and the motto “death is no respecter of persons.”[101] But this message belongs to reconciliation politics and the slogan of the Volksbund and marks its work. The organization tries to reply to the criticism and plans projects like the Soviet cemeteries and concentration camp memorials.[102]

Although the focus is on preservation of graves and on youth projects, from time to time the Volksbund organizes joint field work. For the first time in 2007, the German Army (Bundeswehr) and the Russian Federal Army worked together on the exhumation, burying, and preservation of war cemeteries. The Russian soldiers helped bury Wehrmacht and Red Army soldiers in Lebus, Germany, and took part in the German national remembrance/veterans and mourning day (Volkstrauertag) in the Bundestag.[103] In 2015, Bundeswehr soldiers came to St. Petersburg and, together with their Russian colleagues, recovered the remains of the war dead.[104] After the exhumations, they buried the thirty-eight Germans that were found in the Sologubovka cemetery. The former enemies exhume the dead and bury them together. Does that mean reconciliation?

Reconciliation Over the Graves? Conclusion

The slogan “reconciliation over the graves” applies to a state of understanding, dialogue, and even forgiveness. The case study of Sologubovka showed, though, that reconciliation could not be achieved as planned. The slogan of the Volksbund and its intention to reconcile with the former enemy might be idealistic, but unfinished. The meaning of reconciliation, to pacify with opponents, is not applicable in politics of memory and the postwar relations between two countries. This term stands for something more than the dictionary definition. It stands for an approach, dialogue, and understanding or, to quote the Latin origin, to become friends again or to improve a relationship, to speak again after a conflict or argument. This term does not mean a fixed point after which two parties are reconciled, but rather is a process in which each step follows the other. This process is applicable to the case study in Sologubovka. These steps made by the Volksbund were influenced by their interpretation of reconciliation, by the theological perspective. This perspective[105] the Volksbund supported the finishing of the cemetery complex. These motivations continued in the cemetery’s dedication to peace and reconciliation, within the Peace Park and the Church of Reconciliation. The Russian partners could be reached with the renovation of the church and one of the oldest traditions of humankind: the burying of the dead. Without the encouragement of the priest and the community, the cemetery complex could not be completed. The togetherness of these partners showed dialogue, an understanding, a reconciliation process. The Volksbund, the gardeners, and the villagers in Sologubovka—and even German and Russian veterans[106]—have daily interactions with each other: the application for exhumations at the local authorities, the visiting families and tourists. With respect to these personal relations, it is possible to speak about a reconciliation, an understanding or the attempts for a rapprochement. Regarding relations between states, it looks more difficult. The contemporary sanctions and the political misunderstanding do not support the historical dialogue. Germany should accept Russia’s desire for power, and better integrate the biggest country in the world in European and global politics. Concerning the historical narratives about the war, western Europeans should also accept Russia’s special way and understanding, letting them celebrate the heroes and accept their trauma, which has been burned into the national memory. The war graves could be described as mediators between Germany and Russia.

Hopes and expectations have to be placed on the future. On the one hand, Germany should accept the different narrative, the hero perspective of Russia’s war memory and its need for a national identity and pride. The German partners should be aware of the trauma endured by the Russian people and show more sensitivity to the victim groups such as the Soviet POWs. On the other hand, Russia has to overlook its own national narrative and to look beyond its own interpretation of history. The trauma and the grief should be allowed and topics like the Big Terror, Stalinism, as well as Soviets in concentration camps, the fate of the Soviet POWs, and slave laborers have to be finally processed. The state monopoly on war memory will hopefully break and be transferred to civil society, civil and private foundations, and independent media.

At the press conference after the commemoration ceremony in 2015 at the grave of the Unknown Soldier in Moscow, President Putin spoke about a “rocky path […] between Germany and Russia, the path of tremors and insults to reconciliation.”[107] Truly, the case study of the cemetery shows the rocky path to build a resting place for German soldiers, a place of memory of these men who attacked the Soviet Union and who besieged the city of Leningrad. But this rocky path led to the construction of the Peace Park and the Church of Reconciliation and, in the end, to the finished German memorial complex.

In the end, the complex has been built, but the reconciliation process is not complete. The term does not have a starting and an ending point, but represents a fluid process.

The biggest gesture of the Russians was to permit the Volksbund to build the cemetery near the former Leningrad, the city that represents the greatest losses and the most tragic suffering of the Soviet population.

The headstone has been laid and Sologubovka is the first step for a joint understanding. This joint headstone could be extended in the future to joint memory places, for Germans and Russians. Sologubovka offers therefore the perfect conditions, close to the city of Leningrad, as a symbol for senseless suffering of civilians and for the battlefields around the city; it serves as a reminder of a war of ideologies, racism, and ignorance. Around the village are mass graves and memorials and grave stones. To the Peace Park could be added the names and the remains of the fallen and missing of the Red Army. A model for this idea is “The Ring of Remembrance” in Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, France. At this elliptical war memorial are engraved the names of 580,000 soldiers who died during World War I,[108] alphabetically and not separated by army, nationality, religion, or ideology. This idea can maybe, one day, be transferred to Sologubovka, to remember together World War II and its war dead, beyond all ideologies and nationalities.

Nina Janz was a Harry & Helen Gray/AGI Reconciliation Fellow in August and September 2016. She is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Cultural Anthropology at University of Hamburg.

I would like to thank the following for their support in Germany and Russia: Markus Meckel, Ulla Kux, Stefan Hitzel, Denis Burtnjak, Nele Fahnenbruch, Peter Lindau, Peter Päßler, Silvia Börger and Hans-Dieter Heine, Organization of Ingria, Father Vyatsheslav, the community in Sologubovka, and the church of the Mother in Sphalernaya ulitsa, St. Petersburg. Thank you all for the information, help, and tea! Спасибо!

[1] The terms soldier cemetery or military cemetery are used as well. The term war cemetery represents the groups who are buried on these cemeteries: soldiers, female recruits, female military staff, and refugees such as elderly people and children.

[2] As one of five collective cemeteries in Russia. In total, 813 cemeteries for German war dead, including German POWs, are located in the Russian Federation, www.volksbund.de/kriegsgaeberstaetten (accessed August 22, 2016).

[3] www.volksbund.de/kriegsgraeberstaetten/sologubowka.html (accessed August 22, 2016).

[4] Sologubovka is the final resting place for soldiers not only from Germany, but also from Austria, France (Alsace), Belgium, the Netherlands, and other countries.

[5] The Volksbund started its work after World War I, in 1919, as the so-called Union of the People for the Care of the German War Graves and as a private organization, and is an example of a private organization assuming responsibility for what is usually a state task. During the Third Reich, the Volksbund continued its work building large cemeteries for the fallen of World War I. After 1945, the organization slowly started to work on the grave sites for World War II soldiers.

The Volksbund currently takes care of 832 war cemeteries and graves in 45 countries. The organization is called when other construction on former battlefields reveal human remains. The experts exhume and identify (if possible) the bodies, contact the families (if still alive), and bury the remains in the German cemeteries. Every year more than 30,000 are recovered (see Arbeitsbilanz Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., 2014) Today, several thousand volunteers and 571 salaried employees handle the organization’s various activities. Conferences, seminars, and publications on the culture of commemoration in a European context, educational trips, and trips for relatives are further central pillars of the Volksbund’s reconciliation work. The Bundeswehr—the modern German army—supports the Volksbund by providing practical help at national and international war cemeteries, during the work camps organized by the Volksbund, at commemorative events, and during the annual door-to-door and public donation campaigns.

[6] In German “Versöhnung über den Gräbern.”

[7] The research for this essay is based on archival documents at the Volksbund Archive in Kassel and the Bundesarchiv in Freiburg; research literature; field studies at the cemetery site, at exhumation and excavations projects; interviews with practitioners and field/exhumation experts and witnesses; analysis of media; personal experiences in educational projects of the author; and the analysis of the memory rituals and memory process in both countries. Besides larger studies on France, Poland, and Israel concerning the reconciliation politics, this case study shows one of the first efforts of historical dialogue and the approach between Germany and Russia. The research literature concerning the Volksbund in Russia and its reconciliation work is unsatisfactory. The following is to be mentioned: Elfie Siegel, “Versöhnung über den Gräbern. Kriegsgräberfürsorge in Russland,” osteuropa 58, 6 (2008), 307-316.

[8] Quote in German: “Ein Krieg ist erst dann vorbei, wenn der letzte Soldat beerdigt ist,” in Krieg ist nicht an einem Tag vorbei!: Erlebnisberichte von Mitgliedern, Freunden und Förderern des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V. über das Kriegsende 1945, ed. Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V (Kassel: ggp media, 2005), 7.

[9] frieden, Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., 2 (2015), 7.

[10] A good overview offers Guido Hausmann, “Die unfriedliche Zeit. Der Politische Totenkult im 20. Jahrhundert,” in Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich: Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung, ed. Manfred Hettling, Jörg Echternkamp (München: Oldenbourg Verlag, 2013), 413-439.

[11] In Russian: Никто не забыт, ничто не забыто and part of a poem from the Russian poet Olga Bergholz, a survivor of the siege in Leningrad. Her poem is engraved at the memorial and cemetery for the civilian victims in St. Petersburg, at Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery.

[12] In some aspects Soviet and Russian cannot be separated in the analysis of the national narrative of the Great Patriotic War. The implication of the Soviet time period is still essential in Russian historical memory.

[13] The Great Patriotic War encompasses the war of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union, 1941-1945.

[14] Lev Gudkov, “Die Fesseln des Sieges. Rußlands Identität aus der Erinnerung an den Krieg,” osteuropa 4-6 (2005), 59.

[15] See Nina Tumarkin, The Living & the Dead: The Rise and Fall of the Cult of World War II in Russia (Michigan: Basic Books, 1994).

[16] Nikita Sokolov, “The Forgotten truth about the beginning of the war,” Intersection, 22 June 2016, http://intersectionproject.eu/article/society/forgotten-truth-about-beginning-war (accessed August 23, 2016).

[17] Sabine Behrenbeck, “Between Pain and Silence,” in Life after Death. Approaches to a Cultural and Social History of Europe During the 1940s and 1950s, ed. Richard Bessel, Dirk Schuman (Washington, DC: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 41.

[18] Ibid, 60.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid, 4.

[21] Peter Reichel, “Helden und Opfer. Zwischen Pietät und Politik: Die Toten der Kriege und der Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert,” in Der Krieg in der Nachkriegszeit. Der Zweite Weltkrieg in Politik und Gesellschaft der Bundesrepublik, ed. Michael Greven (Opladen: Leske + Budrich Verlag, 2000), 17.

[22] Ibid, 176.

[23] Gilad Margalit, Guilt, Suffering, and Memory. Germany Remembers its Dead of World War II (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), p. 53

[24] Ibid, 4.

[25] Rüdiger Overmans, Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg (München: Oldenbourg Verlag, 1999), 215.

[26] Margalit, Guilt, Suffering, and Memory, p. 5.

[27] Ibid, 35.

[28] Jan Philipp Reemtsma, “Zwei Ausstellungen – eine Bilanz, redaktionell bearbeitete und gekürzte Fassung eines Vortrags,” Mittelweg 36, 3 (2004).

[29] In October 2016, a joint project between the German Ministry for Foreign Affairs, the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., and the German Historical Institute Moscow will start to digitalize the archival records of the Soviet Prisoners of War; see http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Infoservice/Presse/Meldungen/2016/160622-DEU-RUS-Archivprojekt-Kriegsgefangene.html (accessed September 10, 2016).

[30] Jakob Böttcher, Zwischen staatlichem Auftrag und zivilgesellscaftlicher Trägerschaft. Eine Geschichte der Kriegsgräberfürsorge in Deutschland im 20. Jahrhundert (PhD diss., University of Halle, 2016; not yet published).

[31] Ibid, 202.

[32] While in the Federal Republic greater cemeteries could be constructed, the former Wehrmacht’s graves in the east were neglected. The burial grounds of the soldiers of the Red Army were taken care of instead and were celebrated as liberators and heroes. See Jakob Böttcher, Heldenkult, Opfermythos und Ausöhnung. Zum Bedeutungswandel deutscher Kriegsgräberfürsorge nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/zeitgeschichte/deutschlandarchiv/178572/heldenkult-opfermythos-und-aussoehnung, accessed September 2015.

[33] Behrenbeck, Between Pain and Silence, 57.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid, 59.

[36] The reactions from abroad concerning the German resting places varied. It depends on the country’s experience during the German occupation. France and the Netherlands had strict requirements concerning the construction of military cemeteries. For example “national and military” symbols were forbidden (See Meinhold Lurz, Kriegerdenkmäler in Deutschland, vol. 6 (Heidelberg: 1987), 119). The graveyards in these countries are simpler and contain Christian symbols and chapels. But countries like Tunisia and Egypt, where the civilians were not involved in the battles, allowed bigger monuments. The Volksbund could build memorials in the tradition of the Third Reich. The architect Robert Tischler, who worked in the 1930s and was famous for his nationalist designs, could continue his work in Tunisia and Egypt after the war. He planned the “Death Castles,” for example in El Alemein, in the same design as the monuments of the 1930s, like in Quero/Italy, a cemetery for the German soldiers from the First World War, finished in 1936.

[37] Menschen, die wir lieben, sind niemals tot, ed. Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V (Kassel: 2002), 7.

[38] Deutsche Kriegsgräber in der Sowjetunion. Eine Dokumentation des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. (Kassel: 1983).

[39] Volksbund, “Menschen, die wir lieben”, 11.

[40] Federal Law Gazette (BGBl.) 1991, Part II, 702.

[41] Federal Law Gazette (BGBl.) 1994, Part II, 598.

[42] The German side shows the plans and the designs for the cemeteries to the Russian government and applies for approval.

[43] Federal Law Gazette (BGBl.) 1994, Part II, 598.

[44] Volksbund, “Menschen, die wir lieben,” 14.

[45] Ibid.

[46] About the controversial discussions about the new guidelines and the released guidelines, see: http://www.volksbund.de/volksbund/leitbild/leitbild-des-volksbundes.html

[47] Sebastian Kindler, “Unbekannte Mahnmale in unserer Nachbarschaft. Grabstätten Sowjetischer Kriegsopfer in Deutschland,” published by Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste e.V., Deutsch-Russisches Museum Berlin-Karlshorst, Gegen Vergessen – Für Demokratie e.V., Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas, Stiftung “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft“ (EVZ), Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. (Berlin: 2016), 23.

[48] Ibid, 11, 12.

[49] Ibid, 9.

[50] Ibid, 12.

[51] Cooperation like the German-Russian Museum Karlshorst, German-Russian historian commission, School book, Petersburger Dialog, German-Russian Forum, and especially the German-Russian Youth Exchange (Stiftung Deutsch-Russischer Jugendaustausch).

[52] Press conference President Putin and Chancellor Merkel, 10 May 2015 in Moscow, https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/DE/Mitschrift/Pressekonferenzen/2015/05/2015-05-10-pk-merkel-putin.html (accessed 29 August 2016).

[53] The German Army, after the attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, occupied the region between Schlüsselburg and Leningrad (today St. Petersburg), to cut off the city of three million people from every supply route. The siege lasted for 900 days; over one million civilians starved to death (see David M. Glantz, The Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1944. 900 Days of Terror (London: Cassell Military Paperbacks, 2001). The Red Army fought against the Wehrmacht on battlefields around the Neva River and the cities of Kirovsk and Mga. During the blockade, the Wehrmacht occupied and used the villages close to the frontline as supply depots, hospitals, and cemeteries, such as the village of Sologubovka. The 223rd Infantry Division installed a hospital in the catacombs of the village’s old church; those who died there were buried right next to the church, in total 3,000 German soldiers. After the liberation of Leningrad, on 27 January 1944, the Wehrmacht retreated to the west.

[54] The Wehrmacht constructed hundreds of cemeteries around St. Petersburg during the war. It is impossible to take care of all single graves due to the cost and effort. According to the German-Russian war grave agreement, the remains of the German soldiers have to be exhumed and reburied on a larger collective cemetery in the region, such as Sologubovka.

[55] Today around €97,145.46. Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., Board Meeting (Bundesvorstandssitzung), 20 November 1999.

[56] Steles were used instead of single gravestones due to the high number of losses and costs, Nils Köhler, “Der Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. Versöhnung über den Gräbern: Arbeit für den Frieden,” in Verständigung und Versöhnung nach dem “Zivilisationsbruch”? Deutschland in Europa nach 1945, ed. Corine Defrance and Ullrich Pfeil (Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2016), 431.

[57] Der Tagesspiegel, 27 August 2000.

[58] Interview with Father Vyateslav in Sologubovka, 2 May 2016.

[59] Email from German General Consulate to Volksbund, 2 March 2000.

[60] See footnote 2.

[61] www.gedenkenundfrieden.de/stiftungsarbeit/projekt-solugobowka.html (accessed 24 August 2016).

[62] Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., Main Board Meeting (Bundesvorstandssitzung), 6 March 1999.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., Main Board Meeting (Bundesvorstandssitzung), 20 November 1999.

[65] This exhibition, in German, English, and Russian, names the tragedy of Leningrad and the number of civilian losses. The priest of the church, Father Vyatcheslav, criticizes the Volksbund’s claim to humanize the soldiers and to put the Wehrmacht’s soldiers in a row with the others, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 20/21 September 2003.

[66] Copies of this sculpture are also installed in Nagasaki, Japan and St. Paul, U.S.

[67] Letter of Center for Reconciliation of the City of St. Petersburg to Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., 6 August 1997.

[68] Irina Golonowa, “The Madonna of Nagasaki – Symbol in War or A Memorial for the ‘Heroes of the Fascism’?” August 1997 (not specified). Copy in the document collection at the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., Kassel.

[69] Andrej Wermischew, “The dead are not guilty…but it is better, to install no memorials on German Soldier Cemeteries in Russia,” Newskoje Wremja, 23 September 1997.

[70] Ibid.

[71] The majority of the Soviet cannot be identified.

[72] About war cemeteries and soldier’s burial in Russia in comparison to German war cemeteries, see forthcoming Nina Janz, “Remembering the dead in victory and defeat: The war cemeteries of the Soviet and German soldiers of World War II,” in Views of Violence. Representing the Second World War in Museums and Memorials (Berghahn Press in 2017).

[73] “The dead do us nothing,” Der Spiegel, 43 (1998).

[74] The poll was about the German war cemetery in Sebesh. Sixty-five percent of the listeners supported the cemetery. Siegel, “Versöhnung über den Gräbern,” 308.

[75] “The Right for a proper grave,” TAZ, 7 February 2004.

[76] Frankfurter Rundschau, 2 September 2000.

[77] Donau Kurier Ingolstadt, 12 September 2000.

[78] Tagesspiegel, 27 August 2000.

[79] Ian Traynor, “A corner of Russia that is forever Germany,” The Guerdian, 10 September 2000.

[80] “Schmerzhaft für die russischen Veteranen,” Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeutung, 10 August 2000.

[81] Der Spiegel (36), 4 September 2000

[82] Traynor, “A corner of Russia.”

[83] “Sologubovka,” in Deutsche Kriegsgräberstätten in der Russischen Föderation, Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. and www.volksbund.de/kriegsgraeberstaetten/sologubowka.html (accessed 22 August 2016).

[84] Around 500 active donors.

[85] From the West German perspective; the Volksbund was located in Kassel, in West Germany.

[86] FAZ, 11 September 2000.

[87] Interview with Peter Lindau.

[88] Guest book, in the church; Entry from a German visitor.

[89] Initiative Christen für Europa e.V.

[90] Geert K.M.C. Demarest, “Die Arbeit des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge: Ein Beispiel für die Praxis der deutsch-französischen Aussöhnung 1945-1975,” (PhD diss., Free University Berlin, 1977).

[91] Interview with Hans-Dieter Heine, Head of the Youth Work Department at the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V., Kassel, 26 July 2016.

[92] On the history of the Volksbund and its work see Köhler, “Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge,” 425-442.

[93] Nils Köhler, Hans-Dieter Heine, “Gedanken über Gedenken: Internationale Jugendarbeit in Verbindung mit Kriegsgräbern, in Der Golm und die Tragödie von Swinemunde, ed. Marthe Burfeind, Nils Kohler, and Bernd Aischmann (2011), 447.

[94] Ibid, 449.

[95] Volksbund, “Menschen, die wir lieben,” 11.

[96] Main Board Meeting Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e.V. (Bundesvorstandssitzung), 20 November 1999.

[97] Every year more than 20,000 young people come together in these work camps, in educational and school projects, and in the youth and educational center.

[98] Internationaler Preis des Westfälischen Friedens. The Volksbund and its youth work was the winner in 2014.

[99] Siegel, “Versöhnung über den Gräbern,” 309.

[100] Köhler, “Der Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge,” 436.

[101] President of the Volksbund, Reinhard Führer said: “We are today not the judges of the dead.” See Siegel, “Versöhnung über den Gräbern,” 310.

[102] The participants of the work camp in Sologubovka in 2012 also worked on the Soviet/Russian cemetery nearby, Nevksi Pataschok, according to the report of the camp, Department Organization of the Volksbund in Hamburg.

[103] Materialien zur Friedenserziehungen: Beispiele Praxis. Pädagogische Handreichung: Arbeit für den Frieden, Deutsche und Russen. Wege zur Versöhnung, ed. Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge, 60.

[104] “Versöhnung über den Gräbern,” Deutschland-Radio, 27 August 2015.

[105] Based on Andrew Rigby, Justice and Reconciliation: After the Violence (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2001); John Paul Lederach, Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Countries (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace, 1998).

[106] Before the Volksbund started working in the countries of the former Soviet Union, German and Russian veterans were already in contact, based on private initiatives. Horst Gurlitt, a German veteran (former soldier in the 170th Infantry Division) had private contacts to Russia. He was stationed with his division near St. Petersburg. In memory of his fallen comrades, he wanted to dedicate a memorial stone (text: Here lie German soldiers. We remember them and every missing person in Russia and dead in POW camp”) in Duderhof Nord (Можайский), but a group of civilians demonstrated against it. Instead of this stone, he organized another, smaller sign and engraved “Postamente loquuntur” in 1994. See Bundesarchiv (BArch) MSg 2/6537, “Über den Soldatengräbern wachsen die Bäume,” article by Horst Gurlitt, 1994 and his report “Alte Kameraden,” 1993, BArch MSG 2/6537).

[107] Press conference with President Putin and Chancellor Merkel, 10 May 2015, in Moscow.

[108] Jonathan Glancey, “The Ring of Remembrance, Notre Dame de Lorette,” The Telegraph, 4 September 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/architecture/11220393/The-Ring-of-Remembrance-Notre-Dame-de-Lorette.html.