Herero Activists in the United States: Demanding Recognition and Reparation for the First Genocide of the Twentieth Century

Elise Pape

Maison Interuniversitaire des Sciences de l'Homme -Alsace

Dr. Elise Pape was a DAAD/AICGS Research Fellow in July and August 2017. Dr. Pape completed her binational German-French dissertation in the field of sociology of migration at the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and at the University of Strasbourg, France, in 2012. She has been an Assistant Professor at the University of Strasbourg (2012-2014) and a postdoc at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) in Paris since 2014. Her research interests concern current postcolonial debates in Germany and France, intergenerational transmission in migration processes, social policies, and the use of biographical interviews in social research.

While at AICGS, Dr. Pape conducted research on her project, “Transatlantic Dynamics in Ongoing Postcolonial Negotiations – The Recognition of the Genocide of the Herero and Nama in Germany and in the United States.” The genocide of the Herero and Nama, committed between 1904 and 1908 under German colonial rule in today’s Namibia, is considered the first genocide of the twentieth century. Over the past decades and especially since the commemoration of the genocide’s centennial in 2004, when the German government refused to recognize the crimes committed as such, efforts led by descendants of the survivors to recognize the genocide and negotiate reparations have intensified.

This research focuses on the impact of Herero and Nama activists living in the United States on the ongoing negotiations between the German and the Namibian governments. Based on biographical interviews with Herero and Nama activists living in the United States, it will aim to grasp how the migration path of the interviewees has evolved over time and has affected their strategies, how the U.S. context has impacted their actions and how their transnational experiences and activities have opened up possibilities for transnational or post-national memories.

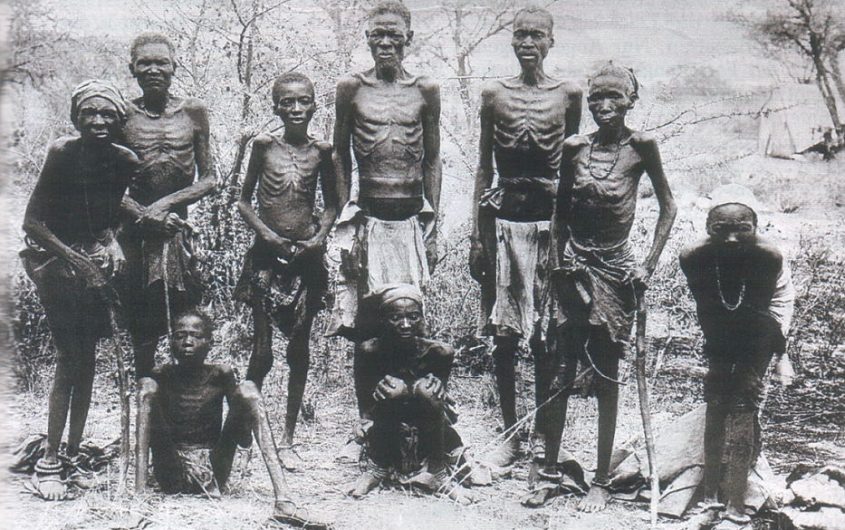

Between 1904 and 1908, over 100 000 people were killed in the first genocide of the twentieth century.[1] Only 20 percent of the Herero and about 50 percent of the Nama survived the mass extermination committed under German colonial rule in today’s Namibia. The German government has never officially recognized the genocide as such. It was not until Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 that protests by descendants of survivors began. Over the past two decades, these protests for the recognition of the Herero and Nama genocide have intensified.

The first transnational conference of Herero and Nama took place in Berlin in October 2016. Its central aim was, among others, to develop a course of action for restorative justice concerning the genocide and its effects. The transnational dimension is central among Herero and Nama, who have lived in a widespread diaspora since the beginning of the twentieth century. Many survivors of the genocide were those who were able to flee Germany’s former colonial territory and reach Botswana and South Africa. Later, during South African rule, numerous Herero and Nama—and other Namibians fighting the apartheid system—left the country as refugees. A considerable number of these former migrants and their descendants still live in the diaspora today. Thus, the delegations of Herero and Nama who attended the Berlin conference in 2016 came from diverse countries, such as Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Great Britain, Germany, and the United States. The Herero and Nama living in the United States seem to play a central role in the current struggle for recognition and reparation by the German government. Certain questions emerged: What was the role of the activists living in the U.S. diaspora in the struggle? How had their migration path evolved over time and how did it affect their strategies? What resources could they draw on in the U.S. context? Did their actions and experiences contribute to developing what Helmut König calls “postnational memories,”[2] memories that question the nation-state and address its more burdensome past?

Herero Living in the United States and the Effects of the Genocide

Today, about 300 Herero live in the United States, making up almost 75 percent of the Namibian population in this country.[3] The members of this group arrived in the U.S. at different times: Most arrived in the 1970s and 1980s as refugees fighting against apartheid, others arrived in the 1990s and later mainly in the course of family reunification or for university studies. While most live on the East Coast, there are also Herero living on the West Coast and in the Midwest and the South. Over the past years, the Herero in the U.S. have founded two main associations: one concerning specific actions regarding recognition and reparation of the genocide, the other concerning cultural actions aimed at the transmission of the Herero culture and language to their children. I was able to participate in two gatherings of these associations through which I met about sixty Herero, whose experiences and opinions inform this essay.[4]

One of the first remarks that struck me was when one interviewee who had arrived in the early 1980s explained that several young Herero migrants had arrived in the U.S. over the past few years and that they “brought new energy in the struggle for the recognition,” as they were “very engaged in the struggle.”[5] As I was later talking to these young twenty-somethings, I tried to grasp what the genocide and its memory meant to them and how it was inscribed in their stories—sometimes as far as five generations after the crimes were committed. Individuals’ answers to this question varied. The strongest answer concerned the physical appearance of numerous Herero. Many interview partners began their life story by telling me about the history of rapes that had taken place in their family’s past. They told about the rapes of their grandmothers, of their great grandmothers, and about the children who had been born out of this sexual violence. In most cases, the fathers were unknown. When they were known and the descendants had tried to contact the other descendants of these men who lived in Germany, they had received no answer. Beginning one’s life story in this way was very revealing. In Namibia, numerous children were born out of relations between German men and Herero women. These were sometimes love relations, but most of the relations were marked by sexual violence. As a result, numerous Herero have very light skin and blue or green eyes. By beginning their life story with the history of rapes that had marked their family, my interview partners were indirectly answering to my surprise—and the surprise of other people they encountered on a daily basis—about their complexions. This theme was omnipresent during my fieldwork. Without my ever addressing this issue, my interviewees constantly evoked it in a very explicit and public way. It was also a very present topic within families. In one of them, in which one of the siblings was very dark skinned, while the other was very light skinned and blue-eyed, the mother asked me: “What do you notice when you see these two brothers?” I thought about what it could mean for the persons concerned to constantly have to justify their physical appearance, and thereby to evoke sexual violence as being part of their history. Contrary to what is sometimes evoked in public debates concerning the Herero and Nama genocide, the memory of the crimes committed will not “fade away automatically.” Concerted reflection and action are needed to bring some closure to this past—and present.

Actions in the Struggle for Recognition and Reparation Undertaken from the U.S.

Since the end of apartheid in 1990, demands for recognition of and reparation for the genocide have intensified among Herero and Nama, with varied results. The genocide has become better known on an international level, leading to an increased interest of researchers in the topic since the 2000s. In 2011 and 2014, over fifty skulls of Namibians found in German anthropological collections were repatriated to Namibia. In 2015, negotiations began between the German and the Namibian governments concerning a possible recognition of the genocide by the German government. Different actions led from the U.S. contributed to these milestones and formed important turning points in the struggle since 1990.

Examples of such actions include the lawsuits filed in 2001 against the German government and German companies that benefited from the genocide in a district court in Washington, DC, and more recently in January 2017 in a district court in New York City. The lawsuit filed in 2001 aimed, above all, to raise international awareness of the genocide. It can be seen, in a way, as the opening event of the debates on the genocide that intensified in the following decade.[6] This increased awareness among civil society of the consequences of German colonial rule contributed to the creation of a wave of “postcolonial associations” in cities throughout Germany that aim to “decolonize” German public spaces and that have also been strongly engaged in the recognition of the genocide.[7]

Another key action initiated through U.S. Herero activists was an online petition launched in 2014 demanding recognition of and reparation for the genocide by the German government. On March 27, 2015, groups of Herero, Nama, and other activists handed over the petition to German embassies in countries such as the U.S., Canada, the United Kingdom, and France. In Berlin, the petition was submitted to a representative of the Foreign Ministry. In July 2015, it was given to the office of the German president. Only a few days later, Bundestag president Norbert Lammert described the crimes committed as a genocide. Although Lammert’s remarks do not constitute an official recognition, the German Foreign Ministry declared that the recognition of the genocide would be on its political agenda. Negotiations began between the German and the Namibian governments that were intended to be concluded before the end of 2016. Before the negotiations started, the German government stated that it would be willing to recognize the genocide, but that no reparations would be made. The fact that one of the negotiating parties defined the outcome of the process even before it had begun triggered protest among the associations engaged in the recognition of and the reparation for the crimes committed. Further protests concerned the fact that the German government only agreed to negotiate with the Namibian government, and not with the groups of victims. Because of the genocide, the Herero and Nama form a minority group in Namibia today and are therefore barely represented in the Namibian parliament. As a result, the Namibian government has not addressed the requests of the victim groups. Furthermore, the Herero and Nama living in the diaspora are not represented by the Namibian government, as they are citizens of other countries. Associations of Herero and Nama have therefore launched the campaign: “It cannot be about us without us. Anything about us without us is against us.”

Resources of Herero Activists in the U.S.

The U.S. context offers different resources to the Herero in their struggle for the recognition of and reparation for the genocide. As mentioned above, one resource is the legal framework, such as the Alien Tort Claims Act, that enables foreign citizens to file lawsuits against governments for human rights violations conducted outside of the United States. The hearing that followed the lawsuit filed in January 2017 has been postponed three times following the absence of representatives of the German government. Diplomatic service is currently aimed between the U.S. State Department and the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A next court hearing is planned for January 2018.

Another central resource consists simply of living outside of Namibia and in a country that allows political freedom. One interviewee explained: “We decided to use the democratic structures here. For example, do petitions at embassies because we can do this here. We have more opportunities to express ourselves. Different Herero went to protest when the [Namibian] president was here, because he did not speak about the genocide. They were not afraid to do that. Because of the freedom of expression. It is risky to do such actions in Namibia, for example if you are a teacher. It is a small country, so you could get difficulties in your professional advancement. At least at the time it was like that.”[8]

Several interviewees also described the economic opportunities in the U.S. that have helped them to fund their political activities. For example, one association is currently raising funds in the U.S. to build a center in Namibia on the Herero culture that will include historical aspects on the genocide.

Another central resource is the possibility of contact and collaboration with other groups of victims and their descendants, especially Jews. In one instance, there was an exhibit and related events on the genocide in a Holocaust museum that involved Herero living in the U.S. The Herero also met with representatives of Jewish organizations in the U.S. who have been engaged in demands for reparations from the German government to victims of the Holocaust. The representatives shared their experiences, successes, and obstacles encountered as well as advice on how to shape ongoing claims and actions. These encounters also offered support in terms of strategies on how to publicly talk about this difficult past. One interviewee, for example, evoked his fear of encountering revisionists of the genocide and the feelings such a position could trigger: “At one of the gatherings, there was a Jewish lady who spoke very openly about what she and her ancestors had experienced. Later, when we were alone, I asked her: ‘How do you do that? Speak so openly? Aren’t you always afraid that there will be someone in the room who will deny that the genocide happened?’ And do you know what she said to me? ‘The cause is bigger than myself.’ I always remember this when I undertake public actions concerning the genocide.”[9]

Several Herero also described a general discourse in the U.S. that was more open to dealing with memory and the effects of genocide. They evoked the “genocide week,” for example, that is part of the curriculum in public high schools in some states, during which students reach out to different representatives of groups of victims and their descendants, in some cases to descendants of survivors of the Herero and Nama genocide.

The resources the Herero activists could draw on in their struggle were two-sided: they used the skills and resources both of their American experiences and of their refugee and migrant experiences. During their anti-apartheid engagement and later their survival in refugee camps, they developed skills on how to develop collective actions, often on a transnational scale, in order to reach their aims. This experience explains the effectiveness of the actions of this relatively small group and its impact on current international political processes.

Postcolonial and Postnational Reconciliation: Working Out Entangled Memories?

Research on reconciliation has stressed the profound changes in international post-conflict interactions and has shown that it has moved from a unidirectional process to processes of dialogue and understanding. The consequences of the Treaty of Versailles have contributed to the strategy of engaging in a dialogue with perpetrators rather than taking revenge on them—a goal of post-World War II relations. Truth and reconciliation committees in this context have increased. This interaction between perpetrators and victims, according to Elazar Barkan, forms a “new form of political negotiation” in which “a new ‘we’ in history is strived for, that includes both winners and losers.”[10] For this process to be possible in the context of negotiations between Namibia and Germany concerning the recognition of and the reparation for the genocide, it seems central that both Namibia and Germany undertake a reflection on the impact colonialism has had on their respective country until today. As stressed by Joachim Zeller, “the process of decolonizing has two sides and cannot only concern formerly colonized states, but also formerly colonizer states.”[11] Perhaps one of the aims of the ongoing negotiations on the recognition and reparation of the genocide should be, as Lily Gardner Feldman shows, to aim “for qualitatively new relations and not the resurrection of old ties.”[12]

Actions to enhance exchanges and dialogue that would make both the German and the Namibian populations more conscious of the effects of colonialism on their societies and to recognize how deeply contemporary social, economic, and political power relations are embedded in this connected history could make a significant contribution to developing such qualitatively new relations. Creating bridges and a new perception of the “Other” could be part of the reparation program of the effects of the genocide. Such an approach was suggested by one interviewee, when she concluded: “What I want is bidirectional access. For example, an exchange between German and Herero kids. In the summer, if these German children want to come to see Herero. Because we are so intertwined.”[13]

[1] For more information see Reinhart Kößler, Namibia and Germany. Negotiating the past (Münster: West. Dampfboot, 2015) and Nick Sprenger, Robert Rodriguez, and Ngondi Kamaṱuka, “The Ovaherero/Nama genocide: A case for an apology and reparations,” European Scientific Journal (June 2017), pp. 120-146.

[2] Helmut König, Politik und Gedächtnis (Weilerswist: Velbrück, 2008).

[3] As the group of Nama in the U.S. appears to be very small, I focused my study on Herero.

[4] I conducted 15 biographical interviews with Herero men and women of different ages and who had arrived in the U.S. at different points in time. Biographical interviews enable researchers to investigate their research questions without imposing their frame of thought on their interviewees, letting them tell their story from their point of view and following their logic.[4] Furthermore, I collected interviews with people who had supported the Herero in their struggle, especially with individuals working in Jewish organizations who were themselves Jewish. More information about the value of interviews is available in Daniel Bertaux, Le récit de vie, 4th edition (Paris: Armand Colin, 2016) and Fritz Schütze, “Biographieforschung und narratives Interview,” Neue Praxis 13 (1983), pp. 283-293.

[5] Interview in New York, July 22, 2017

[6] Kaya de Wolff, “The politics of cosmopolitan memory from a postcolonial perspective,” Entangled memories: Remembering the Holocaust in a global age, Eds. Marius Henderson and Julia Lange (Heidelberg: Winter Verlag, 2017), pp. 387-427.

[7] Elise Pape, “Les débats postcoloniaux en Allemagne – Un état des lieux,” Raison présente, “Colonial, postcolonial, décolonial,” 199 (2016), pp. 9-21.

[8] Interview in Washington, DC, July 16, 2017

[9] Interview in New York, July 25, 2017

[10] Elazar Barkan, The guilt of nations – Restitution and negotiating historical injustices (New York City: Norton, 2000), x.

[11] Joachim Zeller, “Decolonization of the public space? (Post)Colonial culture of remembrance in Germany,” Hybrid cultures – Nervous States. Britain and Germany in a (post)colonial world, Ed. Ulrike Lindner, Maren Möhring, Mark Stein and Silke Stroh (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010), 66.

[12] Lily Gardner Feldman, Germany’s foreign policy of reconciliation: From enmity to amity (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 7.

[13] Interview in New York, July 23, 2017