100 Days of Trump: Transatlantic Relations in Times of Uncertainty

Wolfgang Muno

University of Rostock

Dr. Wolfgang Muno was a DAAD/AICGS Research Fellow in March and April 2017. He is Chair of Comparative Politics at the University of Rostock. Previously, he was a Senior Lecturer at the University of Mainz (habilitation 2015), Acting Professor of International Relations and Comparative Political Systems at University of Landau, Acting Professor of International Relations at Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, and Acting Professor for Political Science at Willy Brandt School. He was Visiting Scholar at University of Ottawa, Canada; at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law SHUPL, Shanghai, China; at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina; at Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas at Austin, USA; and guest lecturer in India, Poland, Norway, Sweden, the UK, and Spain. In addition to his native German, Dr. Muno speaks English, French, and Spanish.

While at AICGS, Dr. Muno worked on a project entitled “Special relationship in flux: Brexit and the future of transatlantic relations.” In June 2016, a shockwave went through Europe: 52 percent of Britons voted in a referendum to leave the EU. The upcoming withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) has since been heavily discussed in Europe. Many studies discuss potential effects of Brexit for the UK as well as for the EU; however, there is much less analysis of what Brexit might mean for wider international relations, especially for the United States and transatlantic relations. The starting point of an analysis of potential effects is a perceived “special relationship” between the UK and the U.S. The main focus of the project is on U.S. perceptions, fears or hopes, or frames; how the United States views Brexit; and on scenarios that are discussed by U.S. foreign policy makers regarding Brexit, and future U.S.-UK, U.S.-EU, and U.S.-German relations.

Much has already been said about Donald Trump’s first 100 days in office, both the style and the substance. Not only has the U.S. seen dramatic policy shifts during this time, but Europe has also witnessed divisive election campaigns and heated Brexit negotiations. It is clear that transatlantic relations—and international relations in general—face turbulent times. Some even see the end of the postwar liberal order. Old wisdoms seem to be worthless in the face of new challenges, and uncertainty is on both sides of the Atlantic.

On the European side, we see the so-called “polycrisis,” a juxtaposition of several crises at the same time, profoundly challenging Europe and European integration. The Euro crisis is not yet solved, and the refugee crisis is ongoing despite no longer featuring prominently in the media. Despite the recent losses of Geert Wilders in the Netherlands and the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) in the presidential elections, the presence of strong anti-European and populist movements has led to ongoing tensions. Brexit is perhaps the most profound challenge. So far, the integration process has been marked by continuous deepening toward an “ever closer Union”—from the European Coal and Steel Community to the Union as codified by the Lisbon Treaty—and by widening—from the six founding members to twenty-eight in 2013 with the accession of Croatia. Now, for the first time, a country is leaving the EU. While the consequences of Brexit are widely discussed, especially what the future EU-UK relationship will be, no one knows exactly what will happen. Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty allows two years for exit negotiations but mentions no further details. Europe is embarking in unknown waters.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the country is adjusting to the Trump administration. Running as the Republican candidate—but explicitly as an outsider, anti-establishment candidate without any experience in politics—Donald Trump’s administration has led to widespread confusion and some amount of speechlessness in the political as well the academic communities. The debate about NATO is one topic that has puzzled transatlantic actors, with the mixed messages between campaigning and governing and a foreign policy that has exhibited a number of detours.

Is NATO Obsolete?

Several times during his campaign and even after taking office, Donald Trump questioned the value and necessity of NATO. In April 2016, Trump made his famous statement that “NATO is obsolete.” He criticized it for unequal burden sharing and accused other NATO countries of “not paying their fair share,” saying, “that means we are protecting them, giving them military protection and other things, and they’re ripping off the United States. Either they have to pay up for past deficiencies or they have to get out. And if it breaks up NATO, it breaks up NATO.”

A second narrative repeatedly used painted NATO as old and outdated, with Trump saying, “It was really designed for the Soviet Union, which doesn’t exist anymore. It wasn’t designed for terrorism.” He then doubled-down on his earlier statement: “I said here’s the problem with NATO: it’s obsolete!”[1]

These statements were cause for concern in Europe. Since taking office, however, the Trump administration’s position has changed significantly. On several occasions, as when British prime minister Theresa May and German chancellor Angela Merkel visited Washington, Trump himself emphasized the importance of NATO and vowed to uphold the military alliance. In January 2017, members of the new administration, as well as members of Congress, repeated this position. Vice President Mike Pence, defense secretary Jim Mattis, and Senator John McCain (R-AZ) reiterated this position publicly at the Munich Security Conference in February. Trump himself stated in a meeting with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg on April 12: “I said it was obsolete. It’s no longer obsolete,” which was a complete U-turn.[2]

Twists and Turns in Trump’s Foreign Policy

Many observers have criticized the inconsistency of Donald Trump’s foreign policy positions during the campaign and in his first 100 days, oscillating between very extreme positions and moderate statements. Thomas Wright of the Brookings Institution spoke of “Trump’s Jekyll and Hyde Foreign Policy.”[3] Some see the new administration turning away from the postwar liberal world order, the set of rules, norms, and institutions created during and after World War II and anchored by the U.S., from Bretton Woods to the United Nations, to NATO and other security alliances, and many international conventions.[4]

The critique of NATO is in line with Donald Trump’s general positions he has publicly upheld for years, including before he ran for president. Thomas Wright sees these positions as part of a “remarkably coherent and consistent worldview” over three decades.[5] He attributes Donald Trump’s foreign policy generally to the nineteenth century. While this criticism may be exaggerated, Wright’s search for patterns in Donald Trump’s foreign policy thinking has yielded valuable results, with those patterns emerging in a long interview Trump gave to Playboy Magazine in 1990 and a 1987 open letter to the American people in a full-page New York Times ad titled “There’s nothing wrong with America’s Foreign Defense Policy that a little backbone can’t cure.”

Together with other analysis, like that of Giovanni Grevi of the European Policy Centre or Walter Russell Mead of The American Interest, it is on this basis that we can identify longstanding patterns in Donald Trump’s foreign policy thinking:[6]

- He has a critical stance toward international alliances, organizations, institutions, partnerships, and multilateral obligations, which imply unfair burdens and costs for the U.S. Military alliances have been seen as especially unbalanced.

- He exhibits a critical view of globalization and “unfair trade deals” that are disadvantageous to the U.S. While previously Japan was the criticized country, in recent times China and Mexico have been the focus of criticism.

- He espouses a nationalist “America First” position, which puts national interest alone on top and sees international politics as zero-sum transactions.

- He believes that, according to his “America First” position, U.S. military power is in decline and has to be restored to counter security threats. While in the 1980s, this was still the Soviet Union, nowadays the primary threat is Islamic terrorism and illegal immigration.

These ideas have been consistent and quite coherent for decades, so the question arises: why did Trump change his position on NATO?

Debates on NATO

NATO enjoys widespread support among parts of the administration, especially the Department of Defense and defense secretary Jim Mattis, who emphasized NATO commitment during his hearings and on his first day in office, as well as by national security advisor Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster. NATO enjoys widespread bipartisan support in Congress, as seen by the Senate’s March 29 vote to confirm Montenegro as the 29th member of NATO, 97-2. Only two senators, libertarian Rand Paul (R-KY) and isolationist Mike Lee (R-UT), opposed Montenegro’s membership, while prominent senators like Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and John McCain (R-AZ) used this opportunity to stress again the overwhelming support NATO enjoys.

While the narrative of “NATO being obsolete” clearly has been dropped by the administration, the second narrative of “fair burden sharing” still prevails. This narrative is not new in U.S. foreign policy and indeed was used by both the Obama administration and Hillary Clinton. In the current administration, Secretary Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson have both reiterated the need for better burden sharing. Secretary Tillerson emphasized this position on March 31, 2017, at his first NATO meeting in Brussels, demanding Europeans spend a minimum of 2 percent of GDP on defense.

Clearly, the debate has shifted from a debate on NATO in general, to a debate within NATO about fair burden sharing. And it is very likely that the latter debate will continue.

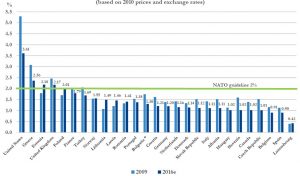

As mentioned, this debate about burden sharing is far from new. At the 2014 Wales summit, NATO unanimously decided to increase its members’ defense spending toward 2 percent of GDP until 2024. Currently, the U.S. spends 3.61 percent, and in Europe, only Greece (2.36 percent), Estonia (2.18 percent), Great Britain (2.17 percent), and Poland (2.01 percent) meet the goal.[7]

Germany spends 1.2 percent, around €34 billion in 2016; spending 2 percent would nearly double defense spending to €70 billion. While the Trump administration maintains the 2 percent goal, a position also backed by Congress, Germany has tried to find loopholes. German leaders have argued that NATO did not decide explicitly and exactly on a 2 percent minimum, but rather only “aimed toward” 2 percent defense spending. They have also argued that security implies more than just defense spending, and German defense minister Ursula von der Leyen and foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel want to include humanitarian aid or development aid as part of a more comprehensive understanding of security. The first argument is simply nitpicking, but the second has its merits and reflects academic thinking about a new, more comprehensive understanding of security, including aspects of soft power. But it seems to be a rather provocative position at the moment, taking into account that Germany agreed to an increase of defense spending in Wales and that defense spending within NATO—and especially within the Trump administration—is clearly defined in hard power terms.

As mentioned, this debate will likely continue. More defense spending in the U.S. and in Europe as part of a fair burden sharing has been and will remain a crucial issue for the Trump administration. On the European side of the Atlantic, rising defense budgets pose serious challenges for governments still struggling with the Euro crisis, refugee problems, and populists who are either completely against NATO or friendly toward Putin (which implies that Russia is not a security threat and, therefore, there would be no need to increase defense spending). Germany, already in campaign mode for the September 2017 elections, is unlikely to commit to such a drastic rise in defense spending as described, but after the elections, the deck may be reshuffled. However, European governments, and especially the EU, should seriously consider more and closer cooperation in defense, as rhetoric in the U.S. has sharpened and criticism has grown.

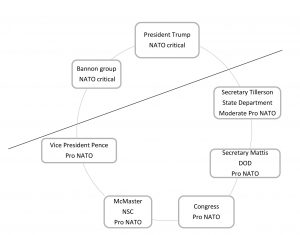

Changes in Security Policy

There are many actors involved in foreign policymaking and alliances. Fissures, rifts, and different factions or advocacy coalitions may explain changes or continuity. One important actor is the president himself, having the last decision. As mentioned, President Trump criticized NATO heavily. Within the White House, there are advisors like Steve Bannon (perhaps associated with Stephen Miller and Sebastian Gorka), who support this critical position. Vice President Mike Pence seems to be more moderate. The National Security Advisor and Secretary of Defense both support NATO. The State Department’s position is not quite clear, but it seems that Secretary Tillerson has finally endorsed the pro-NATO group. Additionally, outside the executive branch, there is very strong bipartisan support for NATO in both Houses of Congress. These actors support NATO and emphasize the importance of NATO while also supporting the 2 percent goal.

Analyst Michael Shurkin, a senior fellow at RAND Corporation, attributed the establishment’s pro-NATO position to the legacy of the Cold War, with important actors, from the military commanders McMaster and Mattis, to senators like McCain and Graham, having a “Cold War mindset.”[8] This explanation may be valid to a certain point, especially to explain the position of the military and older members of Congress, but does not explain why younger members endorse the pro-NATO position, too, or why President Trump or Steve Bannon, who both grew up during the Cold War, did not acquire a “Cold War mindset.”

Whatever the reason ultimately was, a unified establishment has influenced and moderated the White House and the president’s position in the NATO debate. We can assume that the more the establishment is unified and has a coherent position, the more Trump’s beliefs may be moderated. A second example may be Russia, where President Trump seems to have changed, too, under strong pressure. But the big challenge for analysis is that the actors, actor groups, and actor coalitions are still in flux and far from unified. Within the White House, there is an “ideological and ‘House of Cards’-like staff warfare,” as the Washington Post recently wrote.[9] In International trade and economy, actors and positions are far more dispersed than in security. Many administration positions remain unfilled, especially in the State Department, and many other actors—like Jared Kushner, the public, the media, and think tanks—may be involved in other areas of foreign policymaking, so it is still too early to determine the final foreign policy of the Trump administration. Foreign policy positions may change in the future, as they did in the first 100 days, but changes may be reversed again if “Jacksonian” ideologists again gain momentum. The world has to prepare for an era of uncertainty.

[1] Quotes from Ashley Parker, “Donald Trump Says NATO is ‘Obsolete,’ UN is ‘Political Game,’” The New York Times, 2 April 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/politics/first-draft/2016/04/02/donald-trump-tells-crowd-hed-be-fine-if-nato-broke-up/?_r=0

[2] Jenna Johnson, “Trump on NATO: ‘I said it was obsolete. It’s no longer obsolete,’” The Washington Post, 12 April 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2017/04/12/trump-on-nato-i-said-it-was-obsolete-its-no-longer-obsolete/?utm_term=.1945c4e9cef4

[3] Thomas Wright, “Trump’s Jekyll and Hyde Foreign Policy,” Politico, 13 March 2017, http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/03/trumps-jekyll-and-hyde-foreign-policy-214903

[4] See Stewart Patrick, “Trump and World Order. The Return of Self-Help,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2017, p. 52-57.

[5] Thomas Wright, “Trump’s 19th Century Foreign Policy,” Politico, 20 January 2016, http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/01/donald-trump-foreign-policy-213546

[6] See Giovanni Grevi, “Lost in transition? US foreign policy from Obama to Trump,” European Policy Centre Discussion Paper, 2 December 2016, http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_7240_lostintransition.pdf; Walter Russell Mead, “The Jacksonian Revolt. American Populism and the Liberal Order,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2017, p. 2-7.

[7] NATO 2016: http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2017_03/20170313_170313-pr2017-045.pdf. See also graph on NATO defense spending.

[8] See Ryan Migeed, “Trump vs. the Pentagon,” The Washington Diplomat 24 , 4 April 2017, p. 10.

[9] Damian Paletta, “Within Trump’s inner circle, a moderate voice captures the president’s ear,” The Washington Post, 13 April 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/within-trumps-inner-circle-a-moderate-voice-captures-the-presidents-ear/2017/04/13/7a7f87b0-1fa7-11e7-be2a-3a1fb24d4671_story.html?utm_term=.acd67b0060a0