Cory M. Grenier via Flickr

China: From Engine of Growth to Risk Factor

Jörn Quitzau

Bergos AG

Joern Quitzau is a Geoeconomics Non-Resident Senior Fellow at AGI. He is Chief Economist at Bergos, a private bank based in Switzerland. He specializes in economic trend research and economic policy. Joern Quitzau hosts two Economics podcasts.

Prior to his position at Bergos, Joern Quitzau worked for Berenberg in Hamburg (2007-2024) and Deutsche Bank Research in Frankfurt (2000-2006) with a special focus on tax and fiscal policy.

Dr. Quitzau (PhD, University of Hamburg) was a Visiting Fellow at AGI in April 2014 and September 2022 and an American-German Situation Room Fellow in April 2018.

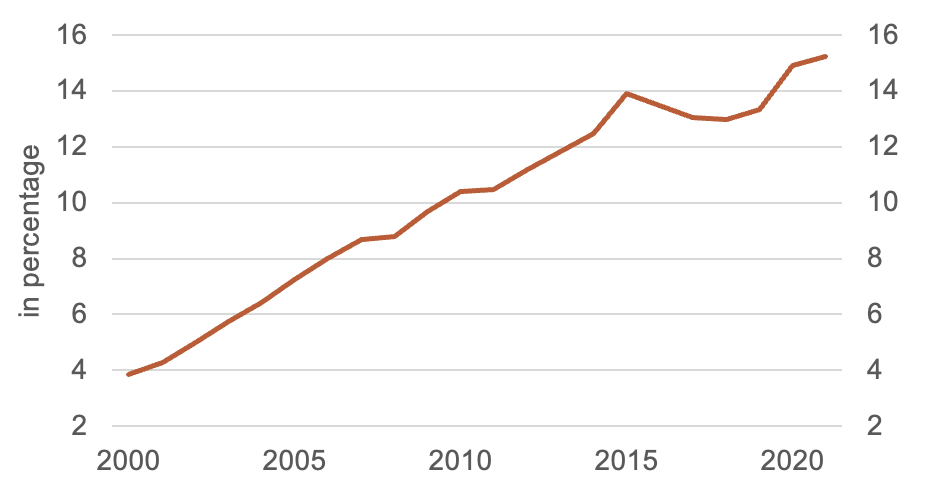

The People’s Republic of China was the engine of global growth and international trade for many years. From 2000 to 2014, China contributed 30 percent to global growth, while its share of global exports rose from 4 percent in 2000 to 14 percent in 2015. China thus rose to become the world’s second-largest economy behind the United States.

Fig. 1: China’s Share of World Exports

Source: IMF, Haver Analytics

China’s rise also plays a major role for Germany. In 2021, the People’s Republic was Germany’s most important trading partner for the sixth year in a row. A total of €246.1 billion worth of goods were traded between the two countries. A look at imports and exports shows that the United States is the main sales market for Germany, while China is eminently important for the German economy, above all as a supplier. The value of all goods imported from China last year was €142.4 billion.

However, it is not only the impressive figures for total imports and exports that make China an important trading partner for Germany—but also for Europe. The People’s Republic supplies a significant number of raw materials and intermediate inputs for important German industries and for technologies that are considered to have a particularly promising future. According to the European Commission, the share of raw materials imported from China into the EU to produce electric motors is 65 percent, for wind turbines 54 percent, and for photovoltaic technology 53 percent.

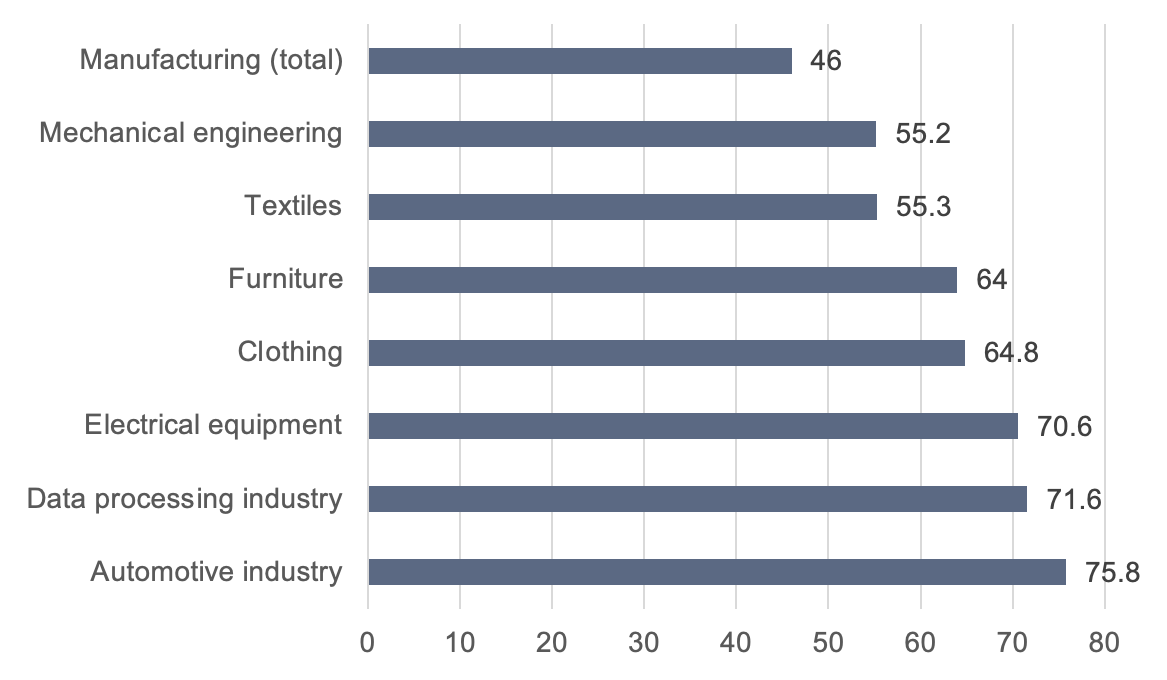

According to a survey by the ifo Institute (using data from February 2022), 46 percent of industrial companies and 40 percent of companies in the trade sector obtain important intermediate inputs from China. Broken down to the individual sectors, companies in the automotive industry (75.8 percent), data processing equipment (71.6 percent), and electrical equipment (70.6 percent) are particularly dependent on intermediate inputs from China.

Fig. 2: Inputs from China, share of German companies in percent

Source: ifo Institute

The success model has had its day

At the same time, there are clear signs that the Chinese boom is over. The forces of growth are weakening, the government stimuli are losing their effect, exaggerations and distortions must be corrected, and thus China is probably no longer the growth engine for the global economy. In a way, it is astonishing that the economic boom could last so long at all. With respect to the convergence hypothesis, it was to be expected that China would converge with the industrial nations as part of an economic catch-up process. Developing and emerging countries benefit from being able to copy the recipes for success of the wealthy industrialized nations. Through adaptation and imitation alone, increases in prosperity can be recorded relatively quickly. Over time, however, the upward forces are often lost so that further growth becomes increasingly difficult to realize. Nevertheless, China has managed to keep growth rates extraordinarily high for a long time––not least with dubious methods such as product piracy and forced technology transfer. With massive subsidies for its own companies, China also gained unfair advantages in international competition.

Ultimately, the economic rise was the result of a peculiar economic model that combines market-based processes with strong elements of a centrally administered economy. Some observers have already sensed an alternative to American-style capitalism, but gradually, more and more weaknesses of this system are becoming apparent.

Government spending, which was supposed to help achieve the ambitious growth targets, has in some cases led to massive excesses, for example in the real estate sector. The Chinese leaders have tried to get some of the excesses under control. Stricter regulations for the construction sector were supposed to curb the exuberance. Now the property market has been deflating for some time but with the usual side effects. The domestic economy and the financial system are being affected. The negative wealth effects weigh on consumption and thus counteract government efforts to strengthen consumption. This puts the government in a dilemma: How can expectations for the real estate market be turned positive again without directly triggering excessive euphoria once more?

All in all, there is much to suggest that growth will remain very depressed for the time being. Also due to the rigid coronavirus policy, growth is likely to reach only just under 3 percent this year and rise to just under 4 percent next year. These are values well below those of the last two decades when economic growth was in double digits at times. Moderate growth is also likely to be the new normal in the longer term. This is not a crash, but it does not make China a real growth engine anymore.

Political imponderables

The economic difficulties are not the end of the story: China is also becoming a political risk factor. The Taiwan conflict makes this particularly clear. Should this conflict escalate, the world economy would have another serious problem. Even if the China-Taiwan conflict calms down again, China remains a challenge for the rest of the world.

In the meantime, it has become clear that the Western industrial nations and China are not only dealing with selective differences in foreign, economic, and social policy. It is about a real system competition with China. There is a lot of ground to be covered on the Western side. How do we deal with a country that massively subsidizes its companies and thus creates unfair competitive advantages in international competition? How do we deal with a country that tramples on human rights and strictly monitors the behavior of its population with the help of a social credit system? A value-based foreign policy can quickly reach its limits when countries are closely intertwined economically but have diametrically different ideas politically. Under normal circumstances, China is an indispensable trading partner for Germany. But are the circumstances still normal?

A new globalization background

The fact is that the view of globalization has changed fundamentally in recent years. Since the beginning of the nineties, globalization has been seen primarily from an efficiency viewpoint. The aim was to reap the wealth gains through the international division of labor that is described in detail in every textbook on foreign trade theory. The darker sides of globalization–distribution problems, dependencies, fragility–were long considered secondary or ignored completely.

With Donald Trump as U.S. president in 2016, the seemingly perfect world of globalization shattered. With his “America first” idea, Trump drew attention to the losers of globalization during the election campaign. He also went on the offensive against China after taking office and later instigated a trade war. At the time, it was still a real shock for the financial markets. Trump’s actions were a turning point for trade policy. Today, a critical view of China is widespread in Washington, DC.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, globalization has come under pressure for quite different reasons: Now, security of supply was at the center of the discussion. The highly interconnected world economy with long international supply chains was suddenly a risk to a country’s security of supply. Already, buzzwords like “near-shoring” and “de-globalization” were doing the rounds.

The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine exacerbated this critical view of international trade, as during the war the prices for food and especially energy shot up to unimagined heights internationally. Moreover, the idea of “change through trade,” according to which authoritarian regimes open politically and socially through trade with democratic systems, got at least deep scratches. Now the buzzword “friend-shoring” is doing the rounds. According to this, there should still be an international division of labor, but only with friendly states that share similar values.

Since the Russian attack on Ukraine, many observers are once again reacting much more sensitively to China. Gone are the days when China was seen primarily as a cheap production location. Now the focus is on the risks emanating from the People’s Republic—economically, socially, and now also in terms of security policy. Ultimately, there has been a 180-degree turn in the view of China. The long-known but often neglected peculiarities of the autocratic system are now being subjected to a renewed analysis, this time probably much more critical. Companies have started to reduce their China engagement.

At the twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party in October, President Xi Jinping further expanded his power. This has brought the imponderables associated with China into the focus of international public attention. A People’s Republic of China striving for an international position of power should probably have been viewed differently much earlier than through our idealizing economist’s glasses, where trade usually takes place quite harmoniously for mutual benefit.