Sandro Halank via Wikimedia Commons

Elections are not Enough

Sven T. Siefken

Institute for Parliamentary Research, Berlin, and Federal University of Applied Administrative Sciences

Sven T. Siefken is professor of political science at the Federal University of Applied Administrative Sciences and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Parliamentary Research (IParl) in Berlin. He is Vice Chair of the Research Committee of Legislative Specialists (RC08) of the International Political Science Association and editor of the German Journal for Parliamentary Affairs (Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen). His current work investigates coalition politics, parliamentary committees and the future of democratic representation. More here: www.siefken.org

Photo credit: APB Tutzing

Negotiating the “Traffic Light” Coalition Contract in 2021

To form a new government in Germany, elections are not enough: first, a coalition must be built to get the necessary votes for electing a chancellor and subsequently forming a government. How this is achieved is not prescribed by the constitution or by any law and thus remains part of informal politics. But through practice, a process of coalition formation has evolved over the decades, becoming more institutionalized along the way. Looking in detail at the organization of coalition formation after the Bundestag election and comparing it to previous years shows that coalition building in 2021 was vertically slimmer and horizontally more differentiated. It followed distinct steps, going through pre-exploratory talks (Vorsondierungen), exploratory talks (Sondierungen), formal negotiations, party approval, and the signing of the coalition contract. The Vorsondierungen were led by the two small parties, the Free Democrats (FDP) and the Greens. Without them, neither of the two feasible coalitions in 2021 was possible, so they decided to take the lead.

Alternating between Shadow and Light in the Process

Party leaders planned and made the entire process of coalition building in 2021 procedurally transparent from the outset. Its elements included backroom negotiations (no longer “smoke-filled,” of course) that were not visible to the public. But negotiators did present intermediate and final results to the media and to party members. In other words, the process alternated between shadow and light. Secrecy in the negotiation phases was particularly noteworthy when compared to the situation in 2017, when many leaks had occurred, sometimes via Twitter from within the negotiation rooms. This time, there was just an Instagram post at the beginning showing the four leaders of the pre-negotiations. Party support was strong. During exploratory talks, party approval was gathered through leadership votes, and formal decisions of SPD and FDP conventions and a digital vote of the Green party members approved the results of the coalition negotiations.

Vertically Slimmer, Horizontally Broader: Complexities of the Negotiation Structure

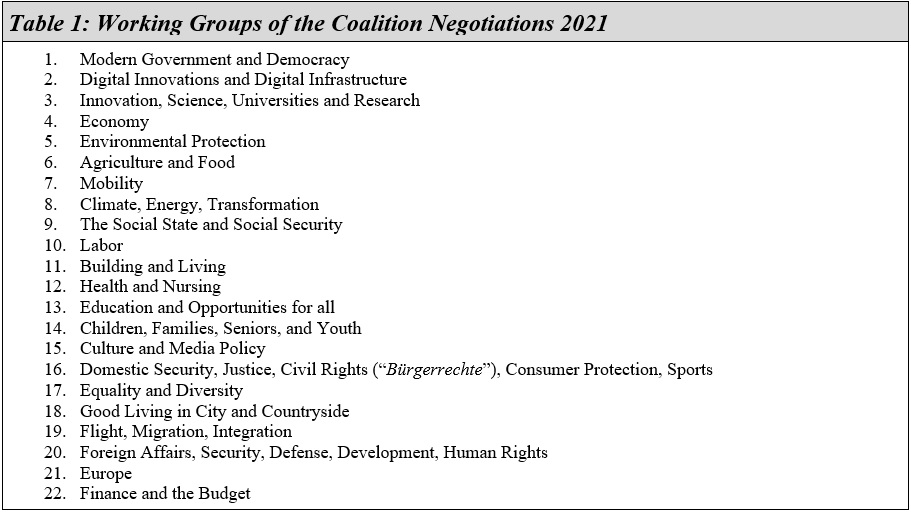

The structure of the 2021 coalition negotiations was also complex. The parties established working groups for the negotiations, and 294 people participated as negotiators. At the core was a main negotiation group with fourteen fixed members, but the details were mostly agreed to in the twenty-two working groups that were structured along different policy areas (see Table 1). Each of them had twelve members, three from each party. Some, dealing with larger topics (economy, climate, social affairs, domestic security, foreign affairs, and finance), were bigger (eighteen members). The working group approach mirrors the use of committees as important units for policy preparation in parliaments. The working groups of the coalition negotiations were tasked to develop a draft paper with a maximum of six pages. Reportedly, the parties even defined the font type (“Calibri”) and font size (11) as well as the line spacing (1.5) up front. All working groups met those requirements, so a draft coalition contract was readily available after the main negotiation group resolved some final issues.

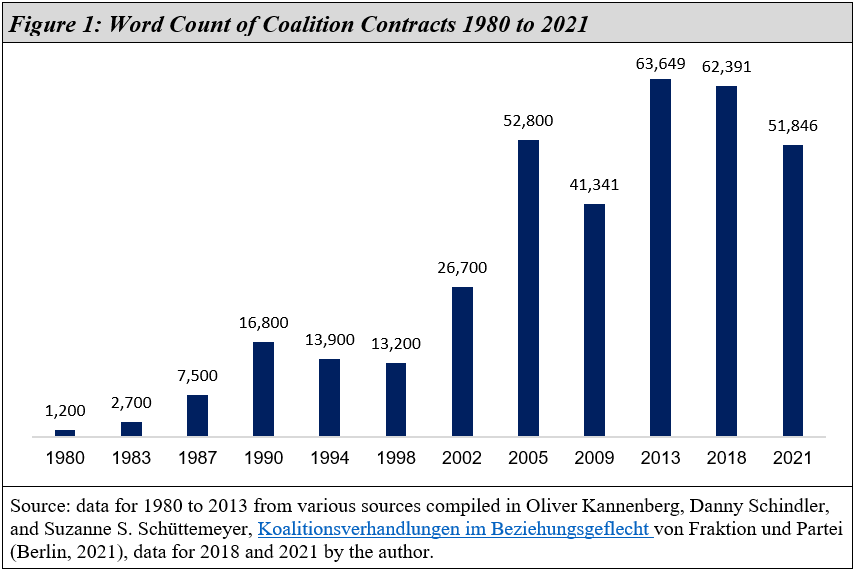

The coalition contract goes into the details of policies and set down the plans for the coalition on 178 pages. This record size is partly due to a generous layout. A word count shows that the coalition agreements in previous years were in fact longer (see Figure 1), although in general coalition agreements have grown far beyond a few pages that were common in the 1980s and 90s. The content is mostly about policy plans, but the agreement also includes provisions for cooperation in the coalition and specific mechanisms for coordination and resolving conflict, most notably through a coalition committee (Koalitionsausschuss)—as had been the practice in the past, too.

Parliamentarization in Process, Structure, and Actors

The process and the structure of the 2021 coalition negotiations reveal inspiration from parliamentary work in the Bundestag. Going back and forth between private negotiations and making intermediate results public mirrors Bundestag processes between committees and the plenary sessions. The horizontal differentiation of policy working groups is similar to the committee structure in most parliaments. And parliamentary actors involved in the 2021 coalition negotiations were also more numerous than before, particularly in the exploratory group (69 percent MPs) and the main negotiation group (79 percent MPs). Yet—just like in the past—coalition negotiations after the Bundestag election are not an exclusive domain of parliament. A sizable number of representatives from the state parties and the state executives, as well as members of the European Parliament participated in the negotiations. Of all the members in the working groups, only 60 percent were members of the Bundestag. This does, in effect, make German coalition building essentially a task of multilevel governance. It may well facilitate the future implementation of the coalition plans in the complex system of multilevel governance in Germany.

What is New and What is Not in the Ampel Style of Coalition Negotiations?

While the coalition building process in 2021 had more procedural transparency than before, its policy debates remained largely out of public view. At defined stages, negotiators obtained party approval through formal votes. Whether the established narrative of personal trust among the involved partners is more than a nice story remains to be seen in the analysis of governing Ampel-style. The first months of 2022 in the handling of the Ukraine crisis indicates that this may in fact not be the case and a very different picture could emerge. What is clear, however, is that the process analyzed in this article did lead to a broad coalition that found overwhelming support in the three involved parties and with a broader public—and this can be partly attributed to the smooth handling of the coalition negotiations.

For more information and detailed sources see: Sven T. Siefken, “Continuing Formalization of Coalition Formation with a New ‘Sound’: Negotiating the Coalition Contract after the 2021 Bundestag Election,” forthcoming, German Politics and Society 40 (2): Summer 2022.