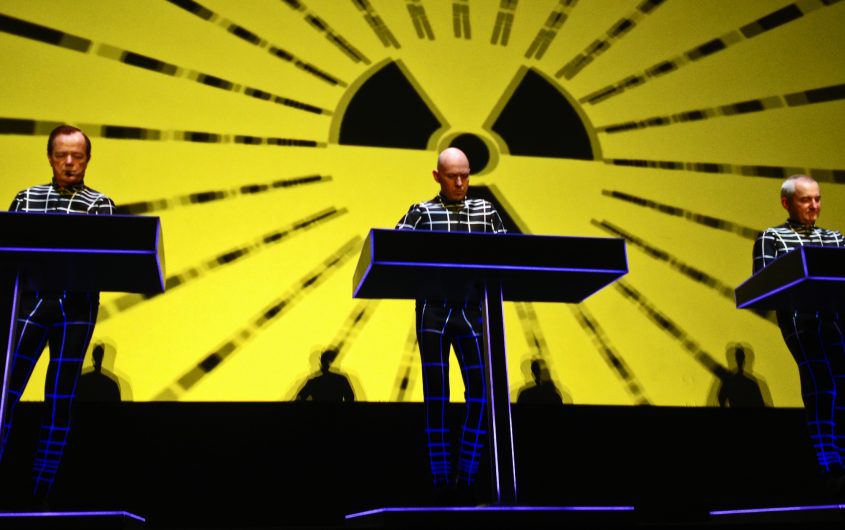

Simon Malz via Flickr

Kraftwerk, the Greens, and Ever-Changing Radioactivity

Steven Ewin

Finance and Development Associate

Steven Ewin is the Finance and Development Associate at AICGS. Prior to joining AICGS, Mr. Ewin worked in a variety of sales and financial positions throughout the public and private sectors. He spent eight years in the United States Army, where he was stationed throughout the world.

He holds a BA in History from Southern New Hampshire University, where his course of study focused on state sovereignty in Cold War Europe. He has completed graduate coursework in Data Analytics and International Relations.

__

Music is the reflection of the society that makes it. One of the most influential musical acts of the twentieth century (second only to the Beatles), Kraftwerk was the defining sound of the Cold War in Germany. Their song “Radioaktivität” (Radioactivity) began as a reflection on the wonder of science. Continuing nuclear accidents, the politics of the Cold War, and fear over what this science could bring, however, would leave a lasting imprint on the German people. Kraftwerk would write these fears into song, updating “Radioaktivität” throughout the decades to express the evolution of German sentiment towards nuclear energy.

The initial version of the song, released in October 1975, approached the subject of radiation with childlike wonder. Kraftwerk approached their vocals as an additional instrument, melding the pitch, sound, and even the style of recording to best blend with the music. Kraftwerk asks the listener to “tune into the melody” that had been “discovered by Madam Curie.” “Wenn’s um unsere zukunft geht” (when it comes to our future) the radio waves provided hope. Yet the original lyrics are unintentionally sinister: radioactivity was “in the air for you and me.” Humanity was now bound to scientific progress, but public opinion took notice of its implications. This implication, that radioactivity was more than happy radio waves, was about to become a core component of German society.

The 1970s saw West German anti-nuclear sentiment grow into a focal point of domestic politics.

The 1970s saw West German anti-nuclear sentiment grow into a focal point of domestic politics. The decade began with the anti-nuclear movement at the fringes of society focused mostly on nuclear weapons and the disposal of nuclear waste. Nuclear energy, as reflected by Kraftwerk, still had potential in many West Germans’ minds. The anti-nuclear movement reached a turning point in 1976, the year after the release of the original Kraftwerk song. The occupation of the proposed nuclear reactor site at Wyhl, originally a local concern of fringe groups, propelled the concerns of nuclear energy to a national issue when the media televised police dragging protestors away. When demonstrators attempted to replicate the occupation in 1977 at Brokdorf and Grohnde, direct conflict erupted between protestors and the police.

By the beginning of the 1980s, the West German anti-nuclear movement coalesced from fringe groups in conflict with authority to a legitimate political movement. Germany was on the path to directly confront its nuclear future already before the Chernobyl disaster unfolded. The American incident at Three Mile Island in 1979 occurred at the same time as an international scientific meeting in Hannover about a radioactive waste disposal facility in Gorleben. The timing of the Three Mile Island incident near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, along with the resultant cancelation of parts of the Gorleben project provided a turning point for nuclear activists. Meanwhile, growing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union ratcheted up the threat of nuclear war. Coming out of this milieu, the Green Party (Die Grünen) formed in 1980 in response to the growing fears that nuclear energy contributed to the destruction of the world. Adopting a mentality from the outset that they were neither left or right but, “in front,” the Greens found a receptive audience. Wearing sweaters instead of suits, by 1983 the Greens held seats in the Bundestag.

Reunification fundamentally restructured German society. The original Green Party merged with their East German counterparts after reunification and had difficulty finding their footing in the reunited nation. Kraftwerk also began to update their catalog. One of the starkest updates involved the 1991 update to “Radioaktivität.” While the original song did not make a value judgment, the updated song took a clear anti-nuclear stance, mirroring the rise of the movement in the previous decade. This update would match the anti-nuclear movement in directness. The disasters at “Tschernobyl, Harrisburg, Sellafield, Hiroshima” are mentioned by name. Further, the song’s chorus clearly stated, “Stop radioactivity” as “chain reaction and mutation” led to a “contaminated population.” It was, after all, still “in the air for you and me.” Shortly after release, Kraftwerk updated the song again for live performances. This version debuted at the 1992 Stop Sellafield-2 event, a concert for Greenpeace to protest the nuclear factory in Sellafield, England. The song began with an eerie voice warning of the effects of the proposed nuclear power plant, including, “Sellafield-2 will release the same amount of radioactivity into the environment as Chernobyl every 4.5 years.”

The 1998 federal election brought the Greens into the majority coalition. In 2002, the Greens succeeded in their legislative mission to remove nuclear energy reactors from Germany by 2020. However, when the Greens left power in 2005, so did parts of their legacy. The CDU/CSU-led coalition government of Angela Merkel delayed the nuclear phase-out by twelve years in 2010. Members of the coalition government had expressed concerns over the price of energy during the transition, and the need for a ‘bridge’ period. This delay, however, would be incredibly short-lived.

Heading into the 2021 Bundestag Elections, the Greens remain a strong contender to serve in government. Far from being a radical party, the Greens—and anti-nuclear energy policies—have become a core component of German society.

On March 11, 2011, the most severe nuclear accident since Chernobyl happened at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan. Two weeks later, the largest anti-nuclear demonstration in German history was held, calling for an immediate shutdown of all nuclear power plants. As always, Kraftwerk would reflect the sentiment of the German public. Playing at the No Nukes 2012 event in Japan a year after the Fukushima power plant disaster, Kraftwerk introduced another major overhaul of the song’s lyrics. Fukushima was introduced into the repeating chant introduced in the 1991 version (switching with Hiroshima). Further, the song had an entire section sung in Japanese. Growing even more direct, the song declared “Radioactivity is in Japan today and forever,” that it is in “the air and water,” and that it needed to “stop now.” This version was officially released in 2017.

Perhaps as responsive to the public’s sentiments as Kraftwerk, the German government recommitted almost immediately to the nuclear energy phase-out. On May 30, 2011, the German government passed new legislation to shut down all nuclear power plants. Unlike the 2002 success, the Greens’ legacy of nuclear phase-out remains secure. Despite rising costs, Germany remains on track for a full nuclear phase-out by 2022 with overwhelming public support. Further, the Greens have continued to grow in influence. They currently are the largest political party in Landtag of Baden-Württemberg (where Green member Winfried Kretschmann serves as Minister-President), and the second-largest in Bavaria, Hamburg, and Hesse. In the 2019 European Parliament elections, the Greens won 20.8 percent of the vote, finishing second in a national-level election for the first time in their history. Heading into the 2021 Bundestag Elections, the Greens remain a strong contender to serve in government. Far from being a radical party, the Greens—and anti-nuclear energy policies—have become a core component of German society.