State Department photo by Ron Przysucha/ Public Domain via Flickr

Richard Grenell: An American Ambassador Leaves Berlin

Stephen F. Szabo

Senior Fellow

Dr. Stephen F. Szabo is a Senior Fellow at AICGS, where he focuses on German foreign and security policies and the new German role in Europe and beyond. Until June 1, he was the Executive Director of the Transatlantic Academy, a Washington, DC, based forum for research and dialogue between scholars, policy experts, and authors from both sides of the Atlantic. Prior to joining the German Marshall Fund in 2007, Dr. Szabo was Interim Dean and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and taught European Studies at The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. He served as Professor of National Security Affairs at the National War College, National Defense University (1982-1990). He received his PhD in Political Science from Georgetown University and has been a fellow with the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and the American Academy in Berlin, as well as serving as Research Director at AICGS. In addition to SAIS, he has taught at the Hertie School of Governance, Georgetown University, George Washington University, and the University of Virginia. He has published widely on European and German politics and foreign policies, including. The Successor Generation: International Perspectives of Postwar Europeans, The Diplomacy of German Unification, Parting Ways: The Crisis in the German-American Relationship, and Germany, Russia and the Rise of Geo-Economics.

In 1959, Eugene Burdick and William Lederer published a best-selling novel, The Ugly American. It was a searing critique of the American professional diplomatic corps and the lack of cultural knowledge and sensitivity of American officials serving in a southeast Asian country. A recent review described the central argument:

The book depicts the rampant arrogance and ineptitude Burdick and Lederer witnessed in the American diplomatic corps in recent years. They criticized American envoys for their unwillingness to learn their new environs, their insistence on knowing what was best for locals without ever speaking a word to them, or for busying themselves with galas or entertaining American officials on visits. “What we have written is not just an angry dream,” the authors wrote in the introduction, “but rather the rendering of fact into fiction” based on the real diplomats they encountered.

The book so impressed then-senator John F. Kennedy that he sent copies to all the members of the U.S. Senate and it proved to be the inspiration for the Peace Corps.

Today the American diplomatic corps is no longer guilty of cultural ignorance of the countries in which they serve; in contrast, they are trained in the nation’s language, history, culture, and politics for over a year before their posting. This is certainly the case for the U.S. Embassy Berlin, in which the best and brightest of the U.S. Foreign Service are posted. With the beginning of the Cold War, the U.S. sent some of its most experienced people to serve as ambassadors and top officials to Germany, people with backgrounds in foreign affairs, business, law, and the military like John McCloy, Kenneth Rush, Vernon Walters, Richard Burt, Robert Kimmitt, and Richard Holbrooke, along with State Department Germany hands like Martin Hillenbrand, John Kornblum, and J.D. Bindenagel.

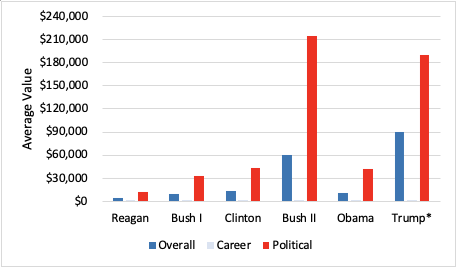

The problem today is not with the Foreign Service, but with the system of political appointees who are given plum postings on the basis of campaign donations rather than deep policy or regional expertise. The Trump administration has hit a new high in this regard, with 45 percent of its ambassadorial appointments going to political appointees. This compares to 30 percent in the Obama administration and 32 percent under George W. Bush, figures which were already too high. Almost all U.S. embassies in Europe are headed by political appointees. The average contribution to the Trump campaign by politically-appointed ambassadors was $189,448. This compares to $12,916 in the Reagan administration. The following chart shows trends in campaign contributions by career and political appointees.

A recent comprehensive comparison of political versus career appointees found the following:

First, since 1980, the average political nominee has been materially less qualified than the average career nominee under a number of standard measures, including language ability, knowledge of the receiving state and its region, and experience in U.S. foreign policy and organizational leadership.

Take, for instance, the issue of language. The certificates suggest that while 66 percent of career nominees possessed a degree of prior aptitude in the receiving state’s principal language, the same was true of only 56 percent of political nominees. […] Upon excluding ambassadorships to English-speaking states, the gap was even larger (56 percent versus 28 percent). In short, a sizable portion of nominees have been completely unable to communicate in the most relevant foreign tongue—and this is particularly true of those who come from outside the foreign service.

Richard Grenell, who announced his resignation as ambassador on June 2, did not get his job through financial contributions, but rather through his work as a media personality and organizer for numerous conservative groups and politicians, most notably as a media assistant for John Bolton during his tenure as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and as a commentator on Fox News. Unlike his Western and Russian counterparts, but like most of his predecessors, he did not speak German but was adept at the uses of new media. He saw his role as ambassador as one articulating an unabashed Trumpian view of the world. He told Breitbart News in a 2018 interview at his Berlin residence, “I absolutely want to empower other conservatives throughout Europe, other leaders. I think there is a groundswell of conservative policies that are taking hold because of the failed policies of the left.”

He did not see himself as a diplomat and has received praise from the right for his advocacy of this worldview: “He’s probably done more television spots than most of our other ambassadors talking back to us about why the president is acting the way he is in Europe and Germany,” said Kiron Skinner, an associate professor of international relations at Carnegie Mellon University and a Fox contributor who served as Director of Policy Planning at the State Department in 2018-19. “I think it’s been very helpful to both sides of the Atlantic.”

The main advantage of a political appointee is that she or he may have the president’s ear and can bring attention to issues in the relationship which the White House can miss. As a former U.S. Ambassador to Germany, John Kornblum,[1] put it:

Rather than grumbling about the different tone of Ambassador Grenell’s statements, it would be better to take advantage of the chance to talk with someone who is not afraid to reflect the President’s views and who has access to his senior assistants. Whether one likes what the Ambassador says or not, he can be an important interpreter between Germany and a President who seems bored with most diplomatic duties.

This was the case with such former political appointee ambassadors as Richard Holbrooke or Robert Kimmitt, whose direct line to the White House was valued by German policymakers. Past American envoys like Vernon Walters, Richard Burt, Holbrooke, and Kornblum have hardly been shrinking violets and challenged the conventional wisdom in Germany. As Henry Nau, has observed, there is a case for Trump’s foreign policy, especially regarding Europe. In Nau’s words,

Overall, Trump’s nationalist/realist policies may be just what the doctor prescribed to sustain the global world order. I say that as an internationalist who would prefer a more value-oriented and less crude approach. Previous presidents talked about sharing burdens and rebalancing trade, yet did little to achieve them. Their internationalist approach reassured allies, and those allies, feeling no pressure, continued to free ride on America’s leadership. Any real change required a root and branch approach. Trump ripped up the ironclad American commitment to global security and world trade—or at least convincingly threatened to do so—and allies and trading partners began paying attention. Now, in a way, the future of globalism depends more on what they do than on what the United States does. After seventy-five years under American tutelage, they will either accept equal global responsibilities in both security and trade, or nationalism will pull them and the United States “back to the future.”

Richard Grenell made this case in a Germany that had been sleepwalking for many years under the cautious leadership of Angela Merkel and a tired Grand Coalition government. Trump’s and Grenell’s frustrations with Germany were shared by the Obama administration as well, and Nau has a point that the less confrontational style of the Obama years and the president’s close relationship with Angela Merkel did not change anything in German policy—although Obama was clearly frustrated with what he saw as European freeriding.

And just because a person is seen as obnoxious does not mean that she or he is always wrong. Grenell had valid critiques to make about such issues as the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline with Russia, and the state of German defense. He was right to raise concerns about Chancellor Merkel’s willingness to allow Huawei to participate in Germany’s 5G network.

Yet he leaves Berlin with the American position in Germany far weaker than he found it. A recent poll supported by the Körber Stiftung shows that 37 percent of Germans found it more important to cooperate with the U.S. while 36 percent preferred working more closely with China. As recently as September 2019, Germans prioritized relations with the U.S. over those with China by a 50-24 margin.

Only 10 percent felt that the U.S. is Germany’s most important partner and only about one-third believed that German-American relations were good compared to two-thirds who believed they were bad. The coronavirus has resulted in the deterioration of the American image for 73 percent of Germans polled compared to 36 percent whose view of China has deteriorated.

Trump more than Grenell is responsible for this decline, but clearly Grenell’s take-no-prisoners approach has alienated the political class in Berlin and the broader attentive public. His openly stated purpose of empowering right-wing forces in Europe clearly crossed the line of what is permissible and wise for diplomats to do, especially in a country with Germany’s past with the extreme right and the current rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD). A number of political leaders called for his recall at various times and he is clearly persona non grata to the chancellor.

A key role of any ambassador is to find ways to make a case for his government’s policies with key decision-makers in the host country. In contrast, Grenell’s only concern was to please his president and in doing so, made it more difficult for Germany to do what the U.S. wants. Any call for increased defense spending is resisted with the rationale that “we won’t do it if Trump is for it.” The same holds on China policy, the new fulcrum for the German-American relationship. Grenell’s open opposition to Huawei has made it more difficult for those Germans, including the security and intelligence services, to oppose Huawei’s growing role in Germany. On Nord Stream 2, American reservations are well founded but the rationale of the Trump administration to block the project is seen in Berlin as based more on the desire to sell American LNG to Germany rather than on sound strategic concern regarding Russian influence. Germany today is not the semi-sovereign West Germany that was totally dependent on the U.S. for its security, a nation trying to recover its self-confidence and looking to America as an ersatz Vaterland or model to emulate. This is no longer the case and a bullying style only sets off the desire for a more independent policy.

Grenell also failed in one of the most critical roles of an ambassador: that of conveying the views and interests of the country in which he is serving. He was a one-way megaphone who did not try to make the case in Washington for a major American ally. Contrast this to the smooth functioning of the two governments during the diplomacy of German unification led by James Baker’s State Department. The American image in Germany has never been as high as it was then. When the relationship hit a low during the Iraq war, diplomats did their job. As one former American official who was involved in German-American relations during German unification and the Iraq war told me:

There are ways of disagreeing without being disagreeable and Grenell failed on this. I know plenty of U.S. FSOs who had to represent the USG’s Iraq policies (during GW Bush) who hated doing it but did it responsibly and avoided unnecessary criticisms of Germany when it didn’t approve of the invasion. This was done to limit damage when the Cheney/Rumsfeld crowd was very angry at Germany. Those diplomats earned their salaries in the face of tough disagreements without breaking the bonds of trust among diplomats, soldiers, and spies. I wonder if there’s as much trust among the professionals in both foreign services now.

Richard Grenell’s exit will not make things miraculously improve. Grenell in a parting tweet stated, “You make a big mistake if you think the American pressure is off. You don’t know Americans.” This has been followed up by his parting gift , the announcement of the unilateral withdrawal of 9,500 American military personnel from Germany, about one-quarter of the total stationed there. The leadership of the U.S. diplomatic mission falls to Charge d’Affaires Robin Quinville, a Foreign Service Officer who is fluent in German and a diplomat with extensive German and European experience. She may have the same brief as her predecessor but will be taken seriously by her German counterparts. She will deliver the message in a professional manner but will lack the connection to the Trump administration’s inner circle. She will be in damage control mode, but that is the best that can be hoped for prior to the American election.

Yet the damage has been substantial and a swift recovery is unlikely.

[1] John Kornblum serves on AGI’s Board of Trustees.