Axel Schmidt/OECD via Flickr

Germany’s Growth Model under Attack?

Björn Bremer

Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies

Björn Bremer is a Senior Researcher in International and Comparative Political Economy at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne. He holds a PhD from the European University Institute and his research lies at the intersection of comparative politics, political economy, and political behavior. He is particularly interested in the politics of macroeconomic policies, welfare state politics, and the political consequences of economic crises.

On his last visit to Berlin in the beginning of May, French president Emmanuel Macron said that “the German growth model has perhaps run its course.” He argued that the economic reforms that Germany made in the early 2000s allowed the country to benefit from imbalances within the Eurozone, but that these imbalances have created problems for the rest of Europe, which are too large to ignore.

These criticisms are not new. For several years, Germany has been attacked for its large current account surpluses, but it resisted rebalancing its growth model in the wake of the European sovereign debt crisis. The German government expected the Southern European countries like Greece, Portugal, and Italy to implement scarring austerity policies and structural reforms, and remained unwilling to write-off debt, boost domestic demand, and rebalance its current account. Germany thus shifted the entire pain of resolving the crisis onto the periphery.

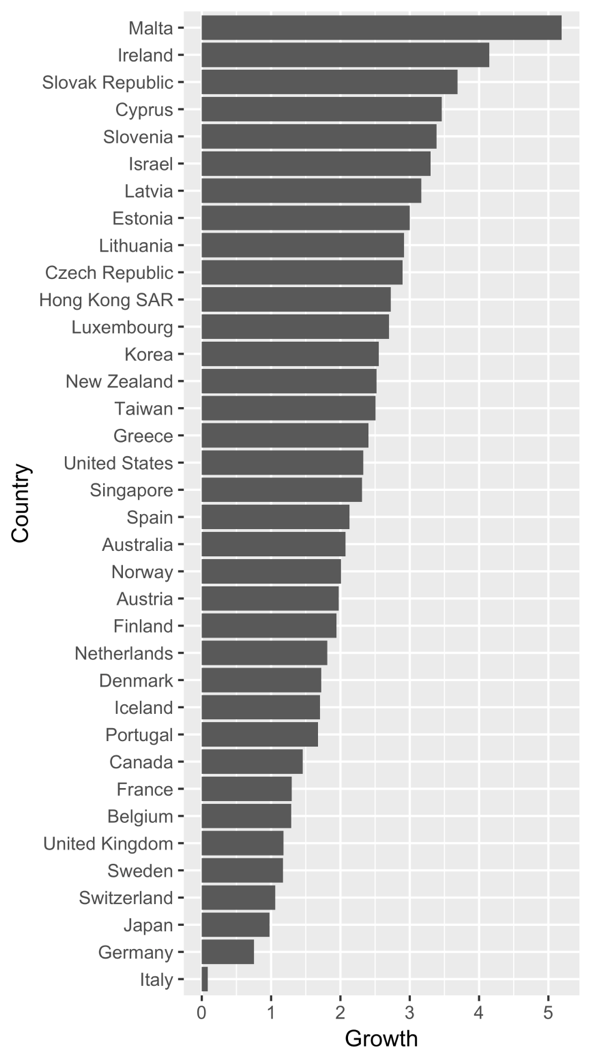

In light of recent evidence, however, Macron’s comments may still be right. Toward the end of 2018, growth in Germany slowed and the growth forecasts are dire. Germany had a small rebound in the first quarter of 2019, but amid continued economic uncertainty Germany’s economic model may still have run out of steam. The IMF forecasts growth in Germany for 2019 to be lower than in all other advanced economies except Italy (see Figure 1).

There are many reasons for this slow down. As Germany has become dependent on exports to China, a possible American-Chinese trade war is threatening Germany’s prosperity, as is Trump’s threat to introduce tariffs on imported cars. Brexit and the political upheavals in continental Europe further create economic uncertainty, but in the long-run, the German economy is even more at risk. The famous Deutschland AG (or Germany Inc.) is stuttering, and its most important export sector—the automobile industry—is lagging behind the innovation frontier.

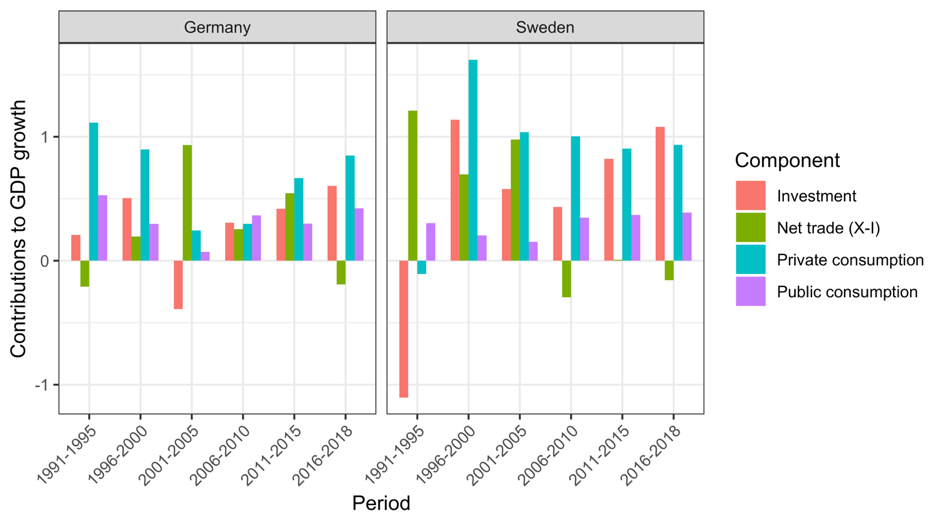

The end of export-led growth, however, may not hit the German economy as strongly as commonly expected. Its current account surplus remains high, but most of its economic growth in recent years has been due to domestic and household consumption, as shown in Figure 2. In the best case scenario, this could be a sign that Germany is quietly moving toward a more balanced growth model. It may follow Sweden’s trajectory in the 1990s. The Scandinavian country first relied on exports to generate growth after its domestic economic crisis, before it successfully combined domestic consumption and exports-led growth (see Figure 2).

Yet, it is uncertain whether Germany can make this shift. According to Lucio Baccaro and Jonas Pontusson, the country’s exports are more price sensitive than Sweden’s. Germany relies on wage moderation to retain the competitiveness of its exporting industry, which makes it difficult to follow the Swedish example: an increase in wages that would spur domestic consumption would directly reduce the competitiveness of Germany’s products abroad. In fact, as Figure 2 shows, the influence of net trade on Germany’s economic growth was already negative in the last three years as wages have slowly increased.

To overcome this problem, Germany faces the tricky task of reducing the price sensitivity of its exports. It needs to shift production toward goods and services into new areas, increasing innovation across a range of sectors. Policymakers can do much to help this process, though: the government should increase public investment in education as well as in research and development, attract high-skilled immigrants, and establish innovation clusters across the country. This would allow Germany to increase consumption while retaining its export strength, reducing the current account surplus, and improving the country’s growth prospects at the same time. Emmanuel Macron would certainly approve of such a plan.