Photo courtesy of Gary Sternberg and the Florence and Laurence Spungen Family Foundation

The Dealer’s Cards: How Gary Sternberg Has Made the Best of Them

Kevin Ostoyich

Valparaiso University

Prof. Kevin Ostoyich was a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2018 and was previously a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2017. He is Professor of History at Valparaiso University, where he served as the chair of the history department from 2015 to 2019. He holds his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and his A.M. and Ph.D. from Harvard University. Prior to moving to Valparaiso, he taught at the University of Montana. He has served as a Research Associate at the Harvard Business School and an Erasmus Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently is an associate of the Center for East Asian Studies of the University of Chicago, a board member of the Sino-Judaic Institute, and an inaugural member of the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum International Advisory Board. He has published on German migration, German-American history, and the history of the Shanghai Jews.

While at AICGS, Prof. Ostoyich conducted research on his project, “The Wounds of History, the Wounds of Today: The Shanghai Jews and the Morality of Refugee Crises.” The Shanghai Jews were refugees from Nazi Europe who found haven in Shanghai, and thus escaped the Holocaust. For this project Ostoyich has interviewed many former Shanghai Jewish refugees and has conducted research at the National Archives at College Park, MD, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At Valparaiso University he co-teaches a course titled “Historical Theatre: The Shanghai Jews,” which fuses the disciplines of history and theatre. To date, students of the course have co-written and performed two original productions based on the history of the Shanghai Jewish refugee community: Knocking on the Doors of History: The Shanghai Jews and Shanghai Carousel: What Tomorrow Will Be. In addition to his work on the Shanghai Jews, he is currently working on projects pertaining to the experiences of ordinary Germans during the bombing of Bremen, German Catholic experiences in nineteenth-century Württemberg, German Catholic migration, and U.S.-German cultural diplomacy during the first half of the twentieth century.

Click here for an article by Ostoyich on the Shanghai Jews.

He is currently trying to interview as many former Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

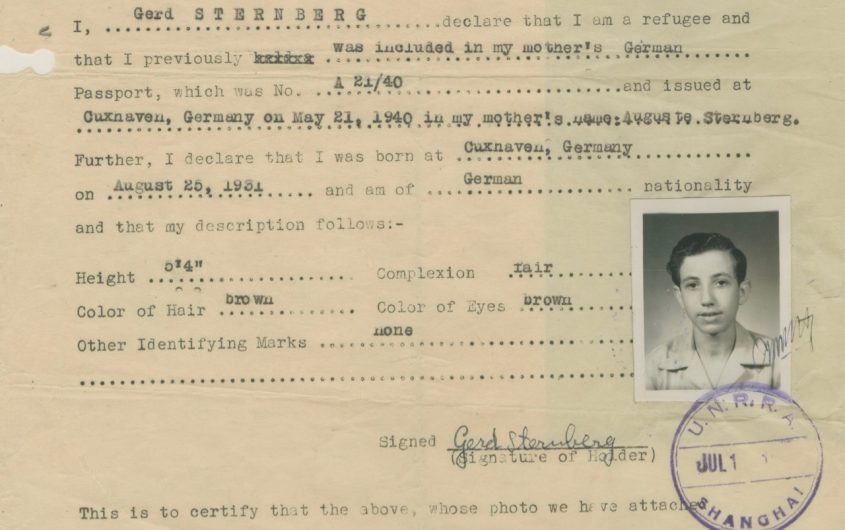

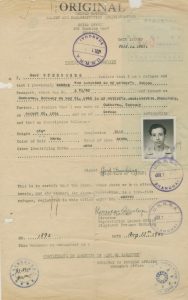

Gerd “Gary” Sternberg was dealt a tricky hand. Born the son of a Protestant mother and a Jewish father in Cuxhaven, Germany on August 25, 1931, he experienced discrimination firsthand in Hitler’s Third Reich. Through luck and perseverance, his family was able to find safety in Shanghai, China. Given that Gary later spent almost 32 years of his life as a blackjack dealer in Las Vegas, he knows a thing or two about luck and the importance of making the best of the hand one is dealt.[1]

Read the stories of other Shanghai Jews

Gary’s father, Hermann, was born on September 2, 1893, in Wetzlar an der Lahn. Gary’s mother, Auguste, was born on November 24, 1894, in Lengoven, in present-day Poland. Hermann and Auguste had come from very different worlds: Hermann from a wealthy family of cattle farmers, Auguste from a modest family of Polish farmers. The more consequential difference between them, and one that would greatly complicate their lives, was that of religion: Hermann’s Jewish faith meant that Hermann and Auguste’s two children, Gary and Ruth, increasingly encountered discrimination even though the children were being raised in Auguste’s Protestant faith. Gary insists, however, that religion was never a point of dissention or disagreement within the family. The Sternbergs celebrated Easter, Passover, Chanukah, and Christmas. Gary remembers the Christmas trees his father would bring home: “The tree is too big or it’s too small, all the branches are one side and over here it’s too bare, it’s crooked on the top, etc., etc.” But he adds that “when the tree was all decorated, it was just perfect.” Hermann was always in charge of setting up the candles for the tree, and buckets of sand and water were placed at the base in case of fire. As Gary remembers, “My father would light the candles and my mother would lead us in song, she had a beautiful voice. The flicker of the lighted candles in the darkened room, the singing and the anticipation of opening the presents was a memorable and festive event.”[2]

Hermann had been a medic during the First World War and had been awarded the Iron Cross for having crawled out of a fox hole in order to save the life of a wounded officer. In Cuxhaven, Hermann maintained an orthopedic practice that he ran out of the house. Gary remembers his father’s workshop, where his father and an employee “would make arch supports, Hernia trusses, artificial limbs, braces and a whole array of medical appliances. It was such a fun place; there were machines, tools and all kinds of materials to make all these things.”[3]

Gary remembers life in Cuxhaven in idyllic terms. The Sternbergs lived on the first floor of a two-story house at Dohrmannstrasse 1, which was just a block away from the North Sea.[4] “There was a big back yard and the side of the house had a flower garden and next to the garden there flowed a creek, it was called ‘Die Wettern,’ the water was usually shallow, very clear and cool, but the current was swift, we had so much fun there, wading bare-footed in the cool water with the mud squishing between the toes, a net in one hand and a tin can in the other we would catch little minnows…”[5] Often Gary and Ruth would walk to the beautiful beach along the North Sea and gaze at Cuxhaven’s famous Kugelbake (a tall structure used by seafarers for orientation). They also watched their step so as not to tred in “Kukake” left like “land mines” by the cows as they grazed the grass.[6] Some of Gary’s fondest memories are those of the family dressing up and going out on beautiful Sunday afternoons, buying ice cream, and listening to bands play “Strauss waltzes and other popular dance music.”[7]

Storm clouds started to appear on the horizon as the 1930s progressed, however. Gary vividly remembers the problems that he encountered in school as anti-Semitism increasingly spread throughout the curriculum. Particularly painful for him was being forced to watch anti-Semitic films, which invariably depicted Jews as criminals and often contained scenes of violence. After one extremely explicit film that ended with townspeople beating up a Jew, Gary went home crying. When he explained the film to his father, Hermann said, “Don’t say anything about it.” Gary remembers his school cancelling all lessons in order to walk to the dike and greet Adolf Hitler as he sailed by Cuxhaven on a yacht: “I would guess that all the schools in town were on that dike. After a while the teachers were going around passing out paper swastika flags. It made quite a sight, the whole dike was bathed in a sea of red, black and white flags. It seemed like we were sitting there for a long time until Hitler’s ship finally appeared way off in the distance. Everybody was disappointed because they expected to at least get a glimpse of that German God. As the ship appeared, we were told that everybody jump to their feet waving their flags and arms and hollering ‘Heil Hitler,’ it was a typical Nazi propaganda spectacle.”[8]

The storm finally hit for the Sternbergs on the early morning of June 14, 1938. Members of the Gestapo banged on the door and carted Hermann away before he even had a chance to say goodbye to Auguste and the children. Gary remembers, “My Mother was hysterical, and my sister and I were crying with all the commotion.”[9] It would be weeks before the family learned that Hermann had been sent to Sachsenhausen.

Although Gary and Ruth were being raised Protestant, they were still viewed by others as racially Jewish. Gary says that he was shunned a lot by the other children. He started to feel this acutely after Hermann was sent to Sachsenhausen: “In school not a lot of kids wanted to befriend me. Because they knew that my father was Jewish. Especially when he went to the concentration camp, that was ‘He’s a Jew. He’s horrible. He’s got horns growing out of his head.’ Yeah, that was hard.” Gary says that up to that time in school he was thought of as being half-Jewish, but after his father was sent to Sachsenhausen, “then the half didn’t count that much; I was just Jewish, and that’s it.”

While Hermann was in Sachsenhausen, men simply showed up at the house and took all of Hermann’s orthopedic equipment, machines, and tools. They claimed they were not stealing the items, but merely “buying it from the Jew, Sternberg.” After loading everything on the truck, “the guy in charge put some papers on the table saying, ‘this is the inventory of all things we bought, sign here’ and with that he threw a few Marks […] on the table and left.”[10] Hermann was released from the concentration camp on January 28, 1939.[11] He and Auguste then tried to figure out what to do. Gary remembers his father saying that the family would have to leave Germany. As he thinks back to his father making that painful decision, Gary is reminded of the similarities of his family to that of Anne Frank. He points out how Hermann Sternberg, like Otto Frank, was a World War I hero, and how both men had to tell their families that they had to leave Germany in search of a haven: “Families being uprooted from beautiful towns and familiar places, leaving friends and possessions behind and becoming refugees overnight. These scenes like the Frank’s and the Sternberg’s were played out thousands and thousands of times, all for the same reason, yet each a completely different story.”[12]

“Families being uprooted from beautiful towns and familiar places, leaving friends and possessions behind and becoming refugees overnight. These scenes like the Frank’s and the Sternberg’s were played out thousands and thousands of times, all for the same reason, yet each a completely different story.”

– Gary Sternberg

Hermann and Auguste were able to find one first-class ticket for Shanghai. Auguste implored Hermann to go, because, as a Jew, he was in the most danger. Somehow Hermann and Auguste scrounged up the money for the expensive ticket, as well as for new clothes that would be suitable for Hermann in first-class passage. During the months in Sachsenhausen, Hermann had lost a tremendous amount of weight and none of his clothes fit him anymore. On May 15, 1939, he left Germany for Shanghai.[13] Auguste then looked for a way to get herself, Gary, and Ruth to Shanghai as soon as possible. Through the generosity of a rich client of Hermann’s, Auguste got a job at a restaurant, and thus managed to provide sustenance for her children as she continued to search for a way out of Germany.[14] Gary remembers that as his mother struggled to make ends meet, money and food were in short supply.[15]

Read the stories of others who escaped to Shanghai

In September 1939, the Germans invaded Poland, thus starting the Second World War. During the next year, Auguste, Ruth, and Gary experienced British bombing raids of Cuxhaven: “Air raid wardens who never had a shred of authority in their lives were now going up and down the streets knocking on doors and shouting orders and telling people what to do, like to tape up the window glass, it had to be done in a crisscross pattern to prevent glass from shattering from bomb blasts, also making sure that drapes were completely closed to black out any light at night. If any light did show through during an air raid you were fined or jailed. Anti-aircraft gun installations and listening posts were popping up all over the place. Military personnel (mostly Navy) was increasing by the day. Officers were strutting around like peacocks.”[16] Gary remembers spending nights in the bomb shelter. “It was scary as hell for a little kid. The bomb shelter was a cement thing and was cold and damp. It was not good […]. Sometimes the bombs got so close that it broke out the windows in the house.” Gary explains, “The favorite thing for all the kids after an air raid was to go around and find bomb fragments and anti-aircraft artillery fragments. Whoever collected the most, of course, was the hero. We used to do that. I had a whole collection of those things.” Auguste continued to work on getting her, Gary, and Ruth out of Germany and on the way to Shanghai. This proved difficult in Cuxhaven, so the three of them moved in with Auguste’s sister and brother-in-law (Annie and Kurt Kasulke) in Berlin. While waiting, the family often had to go down to the basement bomb shelter of the apartment building. Gary remembers that in the shelter people often told jokes that were critical of the Nazi regime. The Minister of Propaganda and Enlightenment and governing official (Gauleiter) of Berlin, Joseph Goebbels, was particularly singled out for ridicule: Gary remembers people calling Goebbels “Halb Sieben”—indicating the hands of a clock at six-thirty—to mock the Minister’s clubfoot appearance. Auguste was shocked at such brazen displays of criticism of the Nazis, but Annie assured her that no one was going to say anything because they were all of like mind.[17] Eventually, in Berlin, and with the help of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Auguste was able to finalize the arrangements for the trip to Shanghai.[18]

Auguste, Ruth, and Gary departed from Berlin and travelled by train through Poland and Russia. Gary remembers going to Moscow, where they stayed in the luxurious Metropol Hotel, and they saw all the sights of the city. They then boarded the Trans-Siberian Railroad at Moscow and continued their long journey. Gary remembers the train being very comfortable with amazing food in beautiful dining cars. His breath was taken away by the scenery of Lake Baikal as the train curved around the lake: “My pastime was to count all the tunnels [that were dug through the mountains], and I counted 53 of them!” His memory of Siberia: “Trees and trees and trees.” When they crossed the border from Russia to Manchuria (at the time, the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo), Japanese soldiers boarded the train, and two soldiers stood guard with fixed bayonets in each car. Gary was frightened and thought they would be arrested. All the shades were drawn and an announcement was made that no one was to look out the windows: “We figured that there were a bunch of Japanese military installations that they didn’t want us to see.” The train took them to Harbin, which Gary remembers being called “Little Israel,” given its large Jewish population. In Harbin they boarded a Chinese train. The conditions onboard were dirty and the smell overwhelming. Sanitation conditions were deplorable, and there were people infested with lice. This was a “total switch” from the conditions they had experienced up to this point on their journey. On the Chinese train, Auguste, Gary, and Ruth first realized what their new lives were going to be like in China. Gary remembers his mother, whom he describes as “a neat freak” being “in total horror.” Gary also remembers that on the train all the signs were in Chinese and English, “which of course we couldn’t read but Muttie [Mommy] had the foresight to bring a little pocket dictionary from German to English and English to German.”[19] The train took them to a port on the Yellow Sea. At the port they boarded a dirty Japanese steamer. Gary remembers they spent three days on this “rusted out rust bucket” to journey to Shanghai. Upon arriving in Shanghai after the long journey, they were greeted by Hermann, who informed them that he had not secured a place for them to stay. Suffice it to say, Auguste was not pleased to learn this. Fortunately, they were quickly able to find a one-bedroom apartment.

The apartment was on the second floor of the building and had a balcony that overlooked a Japanese garrison. From the balcony they could watch the Japanese soldiers doing their exercises with bamboo sticks.[20] Overall, Gary says their relations with the Japanese were favorable, and there even was a Japanese soldier who sometimes brought fruit and meat to Gary’s family.

Given that Gary and Ruth were Christian, they attended a Christian missionary school. Gary says the missionary school placed too much emphasis on religious instruction at the expense of secular subjects, and thus, when he and his sister later had to attend the Shanghai Jewish Youth Association School, they were very far behind the other children in their respective grades.

In 1943, the Japanese set up a “Designated Area” in the Hongkew district. This meant that Gary and his family had to move from their one-room apartment into a camp within the Designated Area. Gary explains, “Shanghai for the most part—pardon the expression—is a shithole, and Hongkew is the shithole of Shanghai.” The camp they moved into was the Chaoufoong Road Camp, which used to be a former Chinese university. Gary and Hermann slept in bunks in the men’s dormitory, and Auguste and Ruth in a large hall. Gary explains the effect on his mother: “My mother went hysterical. There were bedbugs and lice, and it stunk. She went crazy.” A few weeks later, Hermann was able to find a space in a building that was called the “hospital building.” They moved to the third floor of the building. There they lived with four other families in a large room that was only separated with bunk beds and sheets. They only had recourse to communal toilets and cooking facilities. Gary remembers it not being easy, with families bickering and kids screaming all the time.

Gary fell in love with football (American “soccer”) and ping-pong. He explains how if a kid had a football or a ping-pong ball, that kid was popular. “When the ball broke, his popularity waned. So, that was the culture of the camp. [He laughs.]” The children put picnic tables together and put bricks on them to serve as the ping-pong “net.” It did not matter to them that the planks of the tables were all warped. They played football on the field of the former university and had organized teams. The football league was actually quite large. Gary’s team was called Barcelona: “Barcelona was not a good team. We were always along the bottom end of it. We lost every damn game […] and I couldn’t handle that.” Then Gary was asked to play for the Alte Herren Verein (A.H.V.) That was the top team for all the different divisions, from men’s down through the boys. “Just to be on that team—whether you ever played or not—was a great honor.” So, now Gary found out that to play on the team, he needed proper football shoes. The question was how he was going to get them. Gary remembers, “I was in tears because I knew I was going to be dumped from the team because I didn’t have football shoes.” Hermann was able to scrounge up a pair of shoes, but they were too small. Hermann said he thought the shoes were too small, but Gary said, “Oh, no, no. They’re fine! They’re fine!” In actuality he could hardly walk in the shoes. “When they took me off the bench, I could barely walk in those shoes, let alone run or kick the ball. But I still played on the team. [He laughs.] And I was still on the team. It was such an honor even though I couldn’t play worth a damn. With those shoes it was impossible. I was in pain every time we got done with the play. That was my experience playing football.” To this day Gary’s eyes sparkle when he talks about the first-place medal his A.H.V. team won.

The kids improvised when it came to toys and games. They played a game called “Packs” which was like Marbles but with cigarette packs. After the war, the kids added Marbles to their repertoire of games. (They simply could not afford the marbles during the war.) They often made footballs out of rags because actual balls were rare. “Any kid who had a ball was the most popular kid on the block.” They would play on a back lot where there were open sewers. Sometimes the ball would go into the open sewers and they had to go get the ball and wash it off. When they got thirsty, they were not supposed to drink the water. One time when Gary was playing, he got very thirsty and drank from the tap. He got extremely sick afterward with dysentery: “I was so sick. It was unbelievable!” He had to go through many different treatments before getting better.

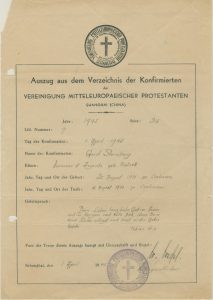

Auguste took the children to church in Shanghai, and it was in Shanghai that Gary was confirmed. Gary explains, though, that he was never really religious. He says there were a lot of mixed marriages among the refugees, but there were also a lot of Christians who had been established in Shanghai well before the refugees arrived. Gary remembers the church not looking much like a church, but just a regular building with services in it. Not being very religious, Gary remembers liking to go to the church simply because he could get cookies there.

Gary says there were other friends in Shanghai who had Jewish fathers and Christian mothers. One such boy whom Gary befriended in Shanghai was Henry Litmanovitz. Although friends in Shanghai, their relationship did not become strong until after both families journeyed to the United States.

Gary remembers being bullied by the Jewish children in the camp. He says, “in Germany I was persecuted for being a Jew, and in Shanghai I’m being persecuted for being a Christian.” He was singled out and called “Jesus Christ.” Thinking back, Gary says, “Kids are kids.”

After the war, Hermann rented a little storefront on Chushan Road.

The family moved out of the camp into a room in a house on Tongshan Road. The lanes stunk and had garbage strewn all over the place, but Gary points out, “that, by comparison, was luxury.” They applied to come to the United States, and “it took us three years total from the time we applied.” In June 1948, the family received visas to go to the United States. One memory stands out prominently for Gary about this process: When it was time for them to go to the American Consulate General to pick up the final documents to travel to the United States, they went by taxi cab. This had become somewhat of a tradition for families to do in celebration of finally getting to leave for the United States. When it was time for the Sternbergs to do this, however, Hermann wavered, saying it was simply too expensive. But Ruth begged and begged until Hermann finally relented. Gary laughs when he points out that the taxi cab did not come to them; rather, they had to walk to the taxi cab and then take it the few blocks to the American Consulate General. “But that was one of those things,” Gary says with a chuckle, “I still think of that today and think it’s funny!”

The Sternberg family then embarked on their journey to the United States. They first set foot on American soil in Honolulu, Hawaii, and the Jewish Community Center there treated them like kings. Gary glows as he remembers, “We couldn’t believe just how they treated us, we felt so important, here little refugees from Shanghai, and they made us feel so important. And they sent each one of us off with a great big bag full of little Hawaiian oranges. Real thin-skinned oranges. And they were like sugar. […] The amount of fruit that we had had was almost non-existent. And here I am, I’m half way through this bag of oranges. I can’t stop eating them. So, when the ship left the harbor, we hit really rough seas. And the ship we were on was an 18,000-ton troop transport and when it hit rough sea the front of the ship would get under the water and then lift up the ocean and then it would rattle […]. I was never so sick in my life. I heaved up all the oranges. And my sister was laughing at me that I got seasick. I might have gotten seasick, but mostly because I was loaded down with those oranges.” Gary remembers going through Pearl Harbor and seeing the masts of the American ships that had been sunk during the Japanese attack sticking up out of the water: “It was an eerie sight.” Gary says his trip on the “slow boat to the United States,” took about two or three weeks. When Gary thinks of his arrival in San Francisco, he chokes up: “That was such a transformation. It’s like coming from Hell into Heaven.” He remembers when the ship approached the Golden Gate Bridge: “It’s enormous. And I’m looking around, I’m asking everybody. And one of the crew from the ship comes up and I asked, ‘where’s the Statue of Liberty?’ And he starts laughing, and I felt like an idiot. He says, ‘You’re in the wrong place. You’re on the opposite side of the country.’ I didn’t know! [Gary laughs.]”

When Gary thinks of his arrival in San Francisco, he chokes up: “That was such a transformation. It’s like coming from Hell into Heaven.”

The Sternbergs were admitted into the United States on July 22, 1948. They stayed in San Francisco for about three months. They had two rooms in a hotel: Hermann and Gary in one, Auguste and Ruth in the other. The family then moved on to Cleveland, Ohio. Gary laughs and says, “For me ‘Ohio’ meant ‘good morning’ in Japanese. But it was Cleveland, Ohio, never heard of it.” On the block to which they moved, they were surrounded by other families of refugees from Shanghai. He recalls, “It was like little Jewish Germany.” Everybody knew everybody else and were generally friendly to one another. One day, Gary ran into Henry Litmanovitz, although Henry’s family had Anglicized their name to Littman. The Littmans moved in two doors down from the Sternbergs. From this point on, Gary and Henry were inseparable. They double-dated and went to parties together. Gary says Henry was a real good-looking guy, and “the girls just flocked around him.” Gary remembers that all he and Henry wanted to do was lose their German accents and become Americans.

Hermann was not able to resume his orthopedic practice. In order to have done so, he would have had to go to school in order to become licensed, and this would have been impossible for him, especially because he did not really speak English. So, Hermann got a job in the Hildebrand Sausage Factory meatpacking plant. Gary remembers his father working hard and how badly this work beat up his father’s fingers and hands.

Meanwhile, Ruth moved to Benton Harbor, Michigan because she had become engaged to an American sailor, whom she had met in Shanghai at one of the dances at the YMCA. Even though Hermann and Auguste were against the union, Ruth married the sailor.

Gary had always been good with his hands, so he got a job with a locksmith and an electrician, who shared a store. Under their tutelage, Gary learned about electricity, radio, locks, and more. Then Gary took a job at a factory that made aircraft parts. Gary started doing backbreaking work carrying long, heavy sheets of steel. He then moved into the inspection division and started taking trade school courses.

In 1952, Gary was drafted into the service. Given his electrical experience, he was put into anti-aircraft radar. After basic training, he was shipped to Korea. At the time, he figured this would be fine, because there were no enemy planes in Korea. The problem, though, was that when he arrived in Korea, he was assigned to the First Field Artillery Observation Battalion. Gary soon found that this “is not a fun job. […] Your life expectancy is not very good.” Gary explains, “We had a big radar stand sitting right behind the front lines with everyone looking down our throat and shooting mortars at us and we had nothing to shoot back with.” His unit’s job was to figure out the trajectory of mortar and artillery shells, plot them out on the map, and then call that information back to an artillery unit, which would then fire on the area. Gary’s unit was sent wherever there was the most artillery fire on the Main Line of Resistance (MLR) that stretched all the way from the west coast to the east coast of the country. The unit was often exposed to the enemy for long stretches of time. He remembers one time this being due to the Korean soil. He explains that the ground in Korea is mostly clay. During the summer the clay turned into powder that would produce a huge cloud if a vehicle went over it, but in the winter, it would turn into a hard rubber substance, and one could hardly dig into it. Gary remembers during the winter his unit was sent up a mountain in central Korea. They could not dig in, so they were completely exposed to the enemy. A group of engineers was sent up to them to try to dig into the ground using dynamite and land mines. After many futile attempts, the engineers simply gave up, leaving Gary and his unit to fend for themselves.

Upon the conclusion of his service in Korea, Gary reflected on how miraculous it was that he had survived bombing raids in Germany and China and then serving in a “four-point zone” (the most dangerous) in Korea. Through it all, the worst injury he sustained was a cut on his leg from running into barbed-wire when he and his friends were fleeing a mortar attack while returning from a movie at Battery Headquarters.

Unfortunately, the same could not be said for Henry Littman. Littman had also been sent to Korea and served as a combat medic. One day Gary was going by Henry’s unit and decided to stop in and see how his best friend was doing. When Gary asked for Henry, he was informed that Henry had been killed a couple days before. Gary was devastated: “I thought I’d sink into the ground.” When he returned home, Mrs. Littman could not even look at Gary because he reminded her of her son. Gary somberly remembers, “It was a horrible, horrible thing. He got killed by small arms fire.” It was not until Gary got married in 1957, that the Littman family was ready to interact with Gary and the Sternbergs again.

In order to marry Noreen Gottlieb, whom he met on a blind date, Gary converted to Judaism. He laughs and says, “Her grandmother didn’t want her to marry a Goy.” At the time Gary was working as a foreman for a spot-welding plant making aircraft parts. Not too long after getting married, Gary and a partner went into business together servicing washing machines and dryers. The partnership eventually broke down, and Gary returned to working at the aircraft parts manufacturer. In 1964, Gary, Noreen, and their daughter, Pammy, moved to Los Angeles with Hermann and Auguste.[21] Not too long after this, Hermann passed away of lung cancer and Auguste died of a heart attack. Gary breaks up when he thinks of the problems he encountered when he tried to have Auguste buried next to Hermann in the Jewish cemetery. The hatred that had flared over the union between a Jewish man and a Christian woman that Gary had witnessed in Germany and China now reared its head again in Los Angeles. Gary stayed his hand and he ultimately was able to prevail in having his parents lay in rest together.

Gary started selling washing machines and stoves for a Sears Roebuck store in Hollywood. As a result, he sold appliances to many stars, including Liberace and Dan Blocker (aka Eric “Hoss” Cartwright on Bonanza). Gary says one of the greatest incentives of working with Sears was the profit-sharing.

After working for Sears for a while, Gary and Noreen decided to start a decorating business called “Driftwood Décor and other Delights,” but despite its catchy name, Gary says, “business didn’t really warm.”[22] After closing the store, and having experienced one too many California earthquakes, Gary and Noreen decided to move to Las Vegas in 1969. The following year Noreen gave birth to the second of their two children, Adam. In Las Vegas Gary opened his own appliance service business. Not too long afterward, he enrolled in Michael Gaughan’s card-dealing school. During the day, Gary ran the business; at night, he learned the art of the deal.

Looking back at all the hands he has dealt and has been dealt, he offers two bits of advice for new players to the table: First: “If you would take religion out of the human equation there would be a lot less death, a lot less killing, a lot less dissension. But this is how things are, so you have to make the best of it.” Second: “The moral of the story of me and so many like me, is, that if you are dealt a bad hand you don’t have to play it, you certainly don’t double down on it or keep on whining about it, you fold or pass and go on till [you] get a good hand and then double down or raise.”

Gary notes that, at the time, to become a dealer at a major casino, one first had to break in downtown, where one did not make much money. Usually, to get a job at Caesars Palace—the greatest casino in the world at the time—one had to work first for about four years downtown. “Obviously, I wasn’t going to go that route,” Gary explains. Instead, Gary played his Ace card: table tennis. During his childhood in Shanghai, Gary had fallen in love with the game, despite the warped boards, brick “nets,” and unreliable balls. In Las Vegas he pursued this passion by starting a table tennis club with students at UNLV. It just so happened that an executive at Caesars Palace, named Neil Smyth, also had a passion for table tennis. Gary said nobody wanted to play with Neil because he had a weird style, but Gary did. Gary asked Neil about working at Caesars Palace, and Neil said that if Gary got a little bit of experience dealing, he could have a job at Caesars Palace. Gary then proceeded to go from casino to casino downtown looking for a job, but only found rejection. Next thing he knew, he got a call from a man by the name of Dick Nee about a busted washing machine. It turned out Dick also had a hot-water heater emergency. Gary fixed both the washing machine and the hot-water heater (despite having little experience working on the latter). Dick was a dealer. Gary asked him if he could help him break in downtown. Dick made a phone call to his friend Marv, a pit boss at the Bonanza Casino. Marv took Gary to see his friend, a casino manager at the El Cortez Casino, who gave Gary an audition and hired him. Gary explains that that is how Vegas works: “Juice.” After Gary worked at the El Cortez for seven months, Neal Smyth carried through on his promise and Gary was granted an audition at Caesars Palace. He passed. He laughs and says, “So, now I’m a big shot dealer at Caesars Palace!” Gary recalls the stress of the first day: “I’m on the game for about two seconds, a guy [sits] down [at my table and says] ‘Let me have a ten-thousand-dollar marker.’ [Gary starts laughing hysterically and shakes to show how nervous he was at the time.]” Gary’s boss came up to him and said, “Gary, if you can’t handle that action, I’ll put someone else on.” Gary said, “No, sir, I can do it, and I dealt away.” For the next 31 years and one month, Gary handled the action. In 2005, at 74 years of age, he put down his dealer’s apron.

Gary says he is very proud of the prestige of having worked at Caesars Palace. He explains, “To some people this may seem like a very minor thing, but to me, a little Jewish boy from China—a little refugee boy—this was a big thing […] to get the best job in a town like Las Vegas.”

While Gary was still working at Caesars Palace, he and Noreen turned to the import business in 1983, but Gary laughs and says, “What do I know about the import business? Not a damn thing!” They started selling sequin and beaded appliques, and business boomed for a few years. “We made good money at it. But then, like anything else, the trend changed—because it’s a fashion item—the trend changed, and we tried different things and invested money in a lot of other things that didn’t work out, and then we finally closed up the business.” Then Gary invented Peeps. Peeps solved the age-old problem of how to protect one’s glasses while having one’s hair dyed at a beauty parlor. “That was the project from Hell. No matter what you can think of that can go wrong with a project. It’s like: You drive your car on the interstate, and you get one flat tire; it’s bad luck, and you pull over to change the tire. But if you drive down the interstate, and get four flat tires; that’s how bad, that’s how unlucky this project went!” The manufacturer sent 50,000 boxes of Peeps—a whole warehouse full—from China, and “half of them were no good, but you didn’t know which half until you tore them apart.” But even with this poor hand, Gary did not bust. A couple years after the shipment fiasco, Gary’s patent attorney called and said that a Danish company had come up with a similar invention and wanted to lease Gary’s patent in order to distribute it in the United States. “I said ‘No way! They’re going to buy it or they’re not going to get it at all!’” Gary sold the patent to the Danes, and still has thousands of boxes of half-defective Peeps.

Peeps is by no means Gary’s only invention. For example, Gary has come up with an efficient and economical transport system for an electric scooter in a vehicle. The inspiration for this was the fact that in the last years leading up to her death in 2002, Noreen was physically impaired, and the available systems for transporting scooters tended to be very complex and expensive. Gary is always tinkering and coming up with new ideas. He is excited about his latest invention—a plexiglass napkin holder for which the patent application is currently pending. The novelty of the holder is that a single napkin can be drawn from the holder with ease. Given that the prototype currently stands on a kitchen table that has been made from an official gaming layout from Caesars Palace, it is not hard to see how the invention could spring from the mind of a man who spent a great deal of his life pulling out one card at a time.

Although Gary Sternberg spent close to 32 years cleanly distributing the cards in Las Vegas, it is clear he has spent his whole life as a dealer. He has always been shuffling the cards, going from Cuxhaven to Berlin to Moscow to Harbin to Shanghai to Honolulu to San Francisco to Cleveland to Los Angeles to Las Vegas. With his trained hands he has shuffled employers countless times: ranging from an aircraft manufacturer, Sears Roebuck, Caesars Palace, and several others. He has dabbled in the worlds of washing machine repair, interior design, and fashion accessories. He has been through bombing attacks in Germany, China, and Korea. He has seen just about every hand imaginable in Las Vegas. Many more articles could be written just on his brushes with Frank Sinatra, Telly Savalas, David Hasselhoff, and many others over the decades. In fact, the transcript of Gary’s interview for an oral history project conducted by UNLV for the history of Las Vegas spans several hundred pages.

Looking back at all the hands he has dealt and has been dealt, he offers two bits of advice for new players to the table: First: “If you would take religion out of the human equation there would be a lot less death, a lot less killing, a lot less dissension. But this is how things are, so you have to make the best of it.” Second: “The moral of the story of me and so many like me, is, that if you are dealt a bad hand you don’t have to play it, you certainly don’t double down on it or keep on whining about it, you fold or pass and go on till [you] get a good hand and then double down or raise.”[23] As for Gary, in 2004, after going on many dates and feeling like he had finally lost all his chips, he met Mary Lou Burbine. With Mary Lou in his life, Gary feels as happy as can be: “I hit the jackpot, and the Lottery, I doubled down and raised the limit and became very wealthy. I am not talking about money…I met Mary Lou: A dealer’s ultimate reward.”[24]

Professor Kevin Ostoyich is a non-resident fellow at AGI. He is associate professor and chair of the Department of History at Valparaiso University (Valparaiso, IN). His research on the history of the Shanghai Jews has been sponsored by the Sino-Judaic Institute (http://www.sino-judaic.org), the Wheat Ridge Ministries – O.P. Kretzmann Memorial Fund Grant of Valparaiso University, the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences, and Dean Jon T. Kilpinen of Valparaiso University’s College of Arts & Sciences. He is currently trying to interview as many Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

[1] The narrative details for the article are based on three interviews conducted of Gary Sternberg by Kevin Ostoyich (October 28, 2017 in Henderson, Nevada; October 28, 2018 phone interview with Sternberg in Henderson, Nevada and Ostoyich in Valparaiso, Indiana; and March 10, 2019 in Henderson, Nevada), additional phone calls, e-mail exchanges, and Gary Sternberg’s unpublished memoir, “The Kid from Cuxhaven: An Autobiography of Gerd (Gary) Sternberg: A Holocaust Survivor’s Story.” In order to keep notes to a minimum, only quotations from “The Kid from Cuxhaven” and e-mails are cited. For a narrative of the family’s history that focuses on Auguste Sternberg, see Kevin Ostoyich, “Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht.”

[2] Gary Sternberg, Unpublished memoir, “The Kid from Cuxhaven: An Autobiography of Gerd (Gary) Sternberg: A Holocuast Survivor’s Story,” (September 20, 2014), 5.

[3] Ibid., 5.

[4] Ibid., 2.

[5] Ibid., 2-3.

[6] Ibid., 3.

[7] Ibid., 4.

[8] Ibid., 9.

[9] Ibid., 10-11.

[10] Ibid., 12.

[11] Ibid., 15. Gary says that later he talked to his father about the latter’s experience in Sachsenhausen. After recounting some of the stories that his father had told him about Sachsenhausen, Gary tears up and says, “It’s unbelievable. Normal, civilized people turned into absolute savages. Savages. Unbelievable.” (Ostoyich interview of Sternberg, March 10, 2019).

[12] Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 17.

[13] Ibid., 18.

[14] The client, Mrs. Reinecke, also sent presents so the Sternbergs could celebrate Christmas with Hermann away in Shanghai: “It was a couple of days before Christmas, Mrs. Reineke’s limousine pulls up to the front door, her chauffeur comes in with his arms full of packages, after his second trip he tells us that Mrs. Reineke and her staff wish us a Merry Christmas while Ruth and I are standing around open mouthed. My mother hugged and thanked him all over the place, and [said] also to thank Mrs. Reineke.” Others also helped the Sternberg family. Gary remembers a baker, who gave Gary a small green wreath along with Christmas wishes for Auguste and Ruth. Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 14.

[15] Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 11. On Auguste Sternberg’s efforts to keep her family alive, see Kevin Ostoyich, “Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht.”

[16] Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 19.

[17] The description of the bomb shelter experience and criticism of Goebbels is based on the interviews as well as Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 24.

[18] On Auguste Sternberg’s efforts to get the family to safety, see Kevin Ostoyich, “Mothers: Remembering Three Women on the 80th Anniversary of Kristallnacht.”

[19] Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 35. Gary still has the little blue dictionary in his desk drawer, and he says, “whenever I open the drawer I can see Muttie leafing through it struggling to construct a sentence.” Sternberg, “The Kid from Cuxhaven,” 36.

[20] Gary explains, “We would watch the Japanese soldiers in competitive judo-like sword combat sport. It is one on one, a bamboo stick would simulate a sword, wearing total bamboo body armor and a baseball catcher’s mask for protection. It was very noisy as they attacked each other with yelling and screaming like a Bonsai charge.” E-mail from Gary Sternberg to Kevin Ostoyich, March 23, 2019.

[21] Pammy was born in 1958.

[22] The name was a riff on Herb Albert’s album, Whipped Cream & Other Delights. Gary attributes the failure of the store to its poor location.

[23] E-mail from Gary Sternberg to Kevin Ostoyich, March 17, 2019.

[24] E-mail from Gary Sternberg to Kevin Ostoyich, March 23, 2019.