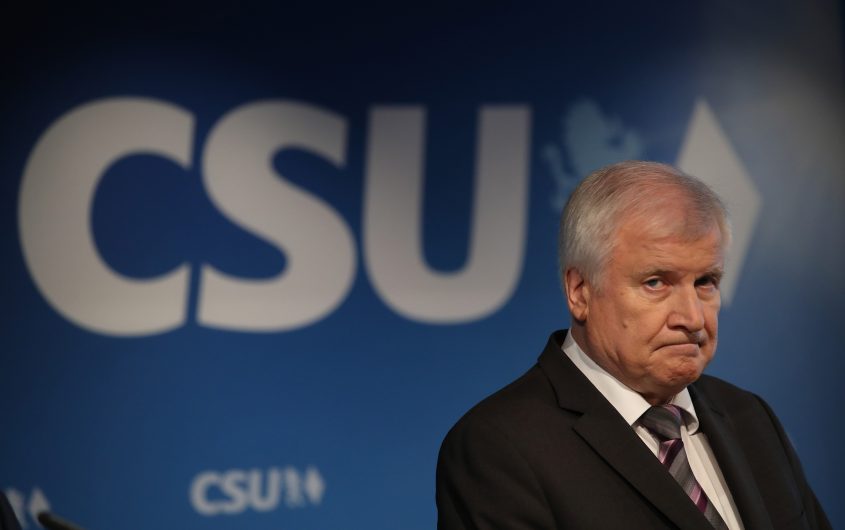

Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Statement of a Polarized Society: The Bavarian Election Results

Michael Weigl

University of Passau

Dr. Michael Weigl is Assistant Professor at the Chair of Prof. Dr. Winand Gellner (Political Science) at the University of Passau. His research focuses on aspects of governance, party systems, and elections (with a special focus on Germany and Bavaria).

A native of Munich, Dr. Weigl worked as a trainee journalist and editor after earning his A levels. He studied Bavarian history, modern history, and political science in Munich. Before joining the University of Passau in 2014, he worked for the Geschwister-Scholl-Institute for Political Science at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich and as head of the Research Group on German Affairs at the Centre for Applied Policy Research Munich.

The results of the October 14, 2018, Bavarian elections mark a watershed in German politics. So far, the Free State has been the last bastion of the conservative Christian Democrats in Germany. For more than fifty years, the Christian Social Union (CSU) dominated the party competition in Bavaria. Since 1966 (with the exception of 2008-2013), the CSU was the sole party in power and—together with its “sister party,” the Christian Democratic Union (CDU)—one of the defining forces of German politics. Now, after the Bavarian election and last year’s federal election, we see the conservative political camp meeting the same fate as befell the other German “Volkspartei” (catch all party), the Social Democrats, fifteen years earlier: Fragmented and weakened, the CDU/CSU is less capable of acting as an anchor of stability in German politics. The Bavarian fortification of conservatism is now weakened—with considerable consequences for the political landscape not only in Bavaria, but also in Germany.

Winning 37.2 percent of the vote (a loss of 10.4 points from the last election), the CSU scored its worst result since 1950, whereas the Greens (17.5 percent, up 8.9 points) became the second strongest force in the Bavarian parliament for the first time. The Social Democrats, who are now only the fifth strongest party in parliament (9.7 percent, down 10.9 points) behind the bourgeois Free Voters (11.6 percent, up 2.6 points) and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD, with 10.2 percent, up 10.2 points), have also experienced a debacle. Since the Liberals also surpassed the 5 percent threshold (5.1 percent, up 1.8 points) that the constitution sets as a precondition for entry into parliament, six parties are now represented in the Munich Maximilianeum—more than ever before.

To explain this historic result, it is not enough to only analyze the election campaigns. Of course the CSU made mistakes. The replacement of the party’s front-runner six months before election day—from the former Bavarian minister president Horst Seehofer to the present one, Markus Söder—was problematic. A minister president always has to fulfill two roles: the powerful party politician and head of state, acting beyond party lines. Söder, however, was seen as a campaigner from his first day in office. He never had the chance to play the appropriate minister president role.

Middle class voters do not want parties that are constantly arguing and squabbling; they expect serious efforts from politicians to solve problems and to seek consensus.

The dispute between the CSU and German chancellor Angela Merkel over migration policy issues in summer 2018 shook voters’ confidence in the CSU’s reliability. Middle class voters do not want parties that are constantly arguing and squabbling; they expect serious efforts from politicians to solve problems and to seek consensus. The dispute with CSU chairman and interior minister Seehofer threatened to end the coalition at the federal level and damaged voters’ confidence in the seriousness of the CSU. It was impossible for the CSU to put other issues on the public agenda after the national dispute and it has increasingly been perceived as a one-topic party, for which the preservation of power is more important than the solution of concrete problems.

However, these explanations are insufficient for explaining the decline of the CSU appropriately, especially since Bavaria is the strongest state in Germany—economically as well as in all other matters. The Bavarian election result is further evidence of the trend toward a deeply polarized society—in Germany and Bavaria, as in most other western democracies—that is leading to a redesign of the traditional party system. At one end of this “continuum of polarization” forming in response to pressures of globalization are those who seek a strong state with closed borders and a distinctive national identity. On the other end are those who advocate for more supranational and international cooperation, permeable borders, and a culture of cosmopolitanism and universalism. Within the German and the Bavarian party system, these two opposite ends are represented by the AfD (entering the Bavarian parliament for the first time) and the Greens. These two groups were effective at appealing to voters’ emotions and then mobilizing voters in the Bavarian elections. The trend right now of demonstrating one’s political stance in public is both strong and distinctive. In such times, the deliberative middle is never attractive.

The fact that in the Bavarian elections both “Volksparteien” lost votes, whereas the other smaller and more specialized parties gained support, is a clear sign of a society in transformation.

The fact that in the Bavarian elections both “Volksparteien” lost votes, whereas the other smaller and more specialized parties gained support, is a clear sign of a society in transformation. It is no longer possible to create a political platform that appeals to all groups within a fragmented society. Nevertheless, in this year’s election campaign, the CSU tried exactly that. The party wanted to appeal to the nationally-oriented right-leaning voter with a restrictive migration policy while also touting welfare and education policy objectives to the liberal, more cosmopolitan voter. As a result, the conservatives lost on both ends of the voter spectrum: The nationally-oriented voters moved toward the AfD and the liberal voters to the Greens and other centrist parties.

One formula for the CSU’s success was to act not only as a regional, but also as a federal political party. With the help of an absolute majority in Bavaria, the CSU was able to set pronounced conservative priorities on the national level. As the Bavarian CSU appeared somewhat more conservative than its CDU “sister party,” both parties complemented one another in campaigning for a broad range of voters. This strategy is now coming to an end. In the future, the CSU can no longer govern Bavaria on its own, but will have to accept a coalition and, consequently, will also have to negotiate federal political matters with its coalition partner. Not only have the conservatives in Germany lost an important voice, but together with the similar decline of the Social Democrats, German politics is losing another voice of the balancing center. Although German democracy is not yet in danger, the result of the Bavarian election should be a warning shot. If, in the future, it is not possible to reconcile opposition factions within society and to represent the interests of all citizens of the democratic spectrum politically, polarization can rapidly turn into a schism.