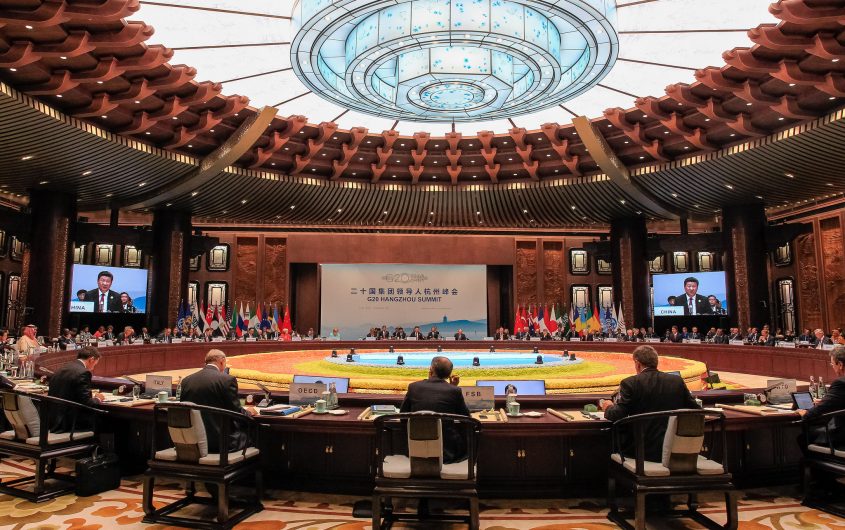

Clauber Cleber Caetano via Flickr

Beijing Knows What It Is Doing…but Do We Know What We Are Doing?

Yixiang Xu

China Fellow; Program Officer, Geoeconomics

Yixiang Xu is the China Fellow and Program Officer, Geoeconomics at AGI, leading the Institute’s work on U.S. and German relations with China. He has written extensively on Sino-EU and Sino-German relations, transatlantic cooperation on China policy, Sino-U.S. great power competition, China's Belt-and-Road Initiative and its implications for Germany and the U.S., Chinese engagement in Central and Eastern Europe, foreign investment screening, EU and U.S. strategies for global infrastructure investment, 5G supply chain and infrastructure security, and the future of Artificial Intelligence. His written contributions have been published by institutes including The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, The United States Institute of Peace, and The Asia Society's Center for U.S.-China Relations. He has spoken on China's role in transatlantic relations at various seminars and international conferences in China, Germany, and the U.S.

Mr. Xu received his MA in International Political Economy from The Josef Korbel School of International Studies at The University of Denver and his BA in Linguistics and Classics from The University of Pittsburgh. He is an alumnus of the Bucerius Summer School on Global Governance, the Global Bridges European-American Young Leaders Conference, and the Brussels Forum's Young Professionals Summit. Mr. Xu also studied in China, Germany, Israel, Italy, and the UK and speaks Mandarin Chinese, German, and Russian.

__

Beijing’s tariff retaliation on Wednesday added more fuel to an already flaring trade war that threatens to put the global economy in jeopardy. Despite breathing a sigh of tentative relief after the Juncker-Trump joint announcement of an EU-U.S. trade reconciliation, the EU and Germany in particular continues to call for a stronger multilateral global trading system. Meeting with Jean-Claude Juncker (European Commission president) and Donald Tusk (European Council president) in Beijing as well as German chancellor Angela Merkel in Berlin last month, Chinese premier Li Keqiang reiterated a shared position that the Trump administration’s unilateral trade protectionist approach is unacceptable. To further illustrate that point, the EU joined China this week to condemn the restoration of U.S secondary sanctions on Iran and instructed European companies to not abide by the U.S. sanctions.

But the torrent of joint criticism is more of an international referendum on the Trump administration’s competence instead of a China-EU coalition against U.S. imperialism, as Chinese media have sought to portrait it. Both Europe and the United States have moved to address their concerns over Chinese economic practices at home and abroad. Chinese president Xi Jinping’s Made in China 2025 plan, which envisions China’s strategic dominance of key industries from artificial intelligence to electric cars to robotics, set off a wave of alarms in the West.

The torrent of joint criticism is more of an international referendum on the Trump administration’s competence instead of a China-EU coalition against U.S. imperialism, as Chinese media have sought to portrait it.

The U.S. Congress passed the Foreign Investment Review Modernization Act, which broadens the jurisdiction of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to include joint ventures, minority stakes, and real estate transactions near military bases or other sensitive national security facilities. The United States’ competitive edge in emerging industries will also fall into CFIUS’ scope of consideration beyond national security risks. In the past, CFIUS rejected proposed takeovers such as Qualcomm and MoneyGram by Chinese companies or entities linked to Chinese interests.

Increasingly concerned about Chinese corporate acquisition in German industrial sectors, the German Bundesrat in April unanimously proposed that the German government lowers the threshold for vetoing foreign investment, which is likely to be lowered from the current 25 percent to 15 percent. In July, the German government exercised its veto power based on security concerns for the first time on a takeover of Leifeld Metal Spinning by the Chinese Yantai Taihai group, which came shortly after the government forced off a Chinese acquisition attempt for 50Hertz Transmission GmbH by directing the state-owned development bank KfW to match the Chinese offer for a 20 percent holding in the power grid operator. Elsewhere in Europe, France, Italy, and the UK are pushing forward their own reforms for foreign investment screening and the EU is on track to adopt an investment screening mechanism.

Xi’s ambitious One-Belt-One-Road initiative (OBOR), a grand Chinese strategy to expand both the country’s economic footprint and its global political influence, continues to provoke concerns in Washington as well as European capitals. But the responses from either side of the Atlantic remain inadequate.

The Trump administration revived the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) together with Australia, Japan, and India last November to serve as the United States’ platform to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific. In his speech to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Indo-Pacific Business Forum, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo outlined the administration’s strategy that seeks to offer an alternative to OBOR. But despite the group’s advocacy for transparency, open competition, robust standards, and sustainability, the U.S. pledge for a $113.5 million fund in digital economy, energy, and infrastructure falls far short compared to the Chinese commitment on its OBOR projects, estimated to top $1 trillion. India, an important partner of the Indo-Pacific Quad, does not participate in the U.S. initiative, and is still weighing potential benefits of closer Chinese-Indian economic engagement. Having extensive trade and investment ties to both Australia and Japan, China has used the carrot and stick approach on both countries to bring them back into Beijing’s orbit of economic and geopolitical interests.

Berlin and Brussels, on the other hand, are increasingly concerned that Chinese influence in eastern and southern Europe is undermining the cohesion of the EU and posing new challenges in its immediate neighborhood. China’s 16+1 initiative, involving eleven central and eastern European EU member states and five Balkan states, promises increased economic cooperation. Despite the fact that the promised investments are yet to materialize and that the Chinese portfolio constitutes only a fraction of overall investment in the region, eastern European governments turn toward their relationship with China for leverage over Brussels. At the same time, governments of Greece, Hungary, and Croatia have shielded Beijing from human rights criticism by blocking joint EU statements. Chinese-backed grand infrastructure development projects in the Balkans, like the Bar-Boljare motorway in Montenegro, threatens to deeply in debt local governments and undermine the prospect of further European integration in the Balkans.

Berlin and Brussels are increasingly concerned that Chinese influence in eastern and southern Europe is undermining the cohesion of the EU and posing new challenges in its immediate neighborhood.

China is now a source of constant challenges as well as opportunity in the foreign and domestic policies of both the EU and the United States. Despite President Trump’s claim that trade war is good and easy to win, attempts to contain or diminish China’s economic activities will hurt the global economy as a whole. But how should the governments on either side of the Atlantic deal with China? Beijing’s long list of initiatives and strategies have served Chinese geoeconomic interests well so far. It often seems the EU and the United States lack the resources and coherent strategies to respond.

Part of the answer may lie in the old phrases of values and ideologies. Beijing has long used its growing economic weight to advocate for a pragmatic, bilateral approach to international relations. For decades, Europe and United States have favored economic engagement with China over an ideology campaign, hoping that more economic development would eventually lead to political reforms and greater openness. That has been proved a false assumption. Furthermore, China’s success has inspired other countries to follow suit and created challenges for the EU and the United States at home and abroad. In order to commit more resources over the long term to promote a liberal, rule-based international order, the West needs to emphasize its commitment to democratic, liberal values, which stand in contrast with China’s rejection of universal values. However, that does not mean that the West should reject Chinese initiatives in a wholesale manner. Europe and the United States should seek to insert their presence by pushing for joint financing through international institutions, open competition, and robust standard-setting in Chinese-led projects like OBOR, which can enhance regional infrastructure connections and bring about much needed industrial development. Most important is that the EU and the United States need to work closely together and with other allies to face challenges and opportunities brought upon by expanding Chinese engagement worldwide. The EU-U.S. reconciliation on trade and investment is a welcome sign toward that goal. But we need more transatlantic cooperation to realize a qualitative transformation in our approach to China.