Life after Merkel?

Dan Hough

University of Sussex

Dr. Dan Hough is a Professor of Politics at the University of Sussex in the UK. His research focuses on party politics, corruption and anti-corruption. In terms of German politics, he's written one single-authored book on the Party of Democratic Socialism (the Left Party's predecessor) and one co-authored (with Jonathan Olsen and Michael Koss) book on the Left Party.

A well-known German comedian once sang a song about the state of Thüringen decrying the Land’s apparent anonymity. “Thüringen,” bemoaned Rainald Grebe, “is a Land that David Bowie once flew over.” It’s also a place “full of walkers wearing very long red socks” and where Heike Drechsler, one of the superstar 1980s East German athletes, “regularly used to jump over seven metres.” For many Germans, Grebe’s got a point—not much seems to happen in Thüringen, and the things that do happene are things that Germans, putting it bluntly, don’t really care too much about.

The regional election that took place on 14 September 2014 in the 2.1 million -strong state would normally be an event that nicely fitted that pattern. Since unification, and the creation of the state out of the rubble of the GDR, Thüringen’s politics has been run for the most part neatly and tidily. The current Ministerpräsidentin, Christine Lieberknecht, is credited with overseeing an efficient and effective administration. Much like Angela Merkel a few miles north in the capital Berlin, she is both liked and respected, and she is widely believed to have done a lot to keep Thüringen’s economic statistics moving in the right direction. But, also like Merkel, Frau Lieberknecht now faces a strategic dilemma; the collapse of the CDU’s long-preferred coalition partner, the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the rise of the Euro-critical Alternative for Germany (AfD) means that the CDU’s options for retaining power are much reduced.

The Results by the Numbers

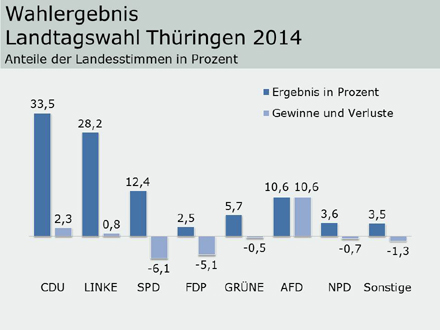

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the normally overlooked state of Thüringen. Following the recent regional election there the CDU remains by a distance the strongest party, improving on its 2009 performance by 2.3 percent to register 33.5 percent. The Free Democrats performed predictably dismally, dropping out of the regional parliament with 2.5 percent of the vote, leaving the social democratic SPD (12.4 percent), the socialist Linke (28.2 percent), and the Greens (5.7 percent) as the CDU’s mainstream opponents. The rise of the non-coalitionable AfD (10.6 percent) further complicates matters.

Thüringen as a Barometer for Berlin

So far so parochial. The dynamics of the election in Thüringen are nonetheless interesting for non-party-political-anoraks for two reasons. Firsty, for the most part they mirror developments in Berlin; the FDP appears to be on the verge of non-existence, the AfD looks like it is in for the long haul and the CDU is stuck with the—largely unattractive—option of entering in to a grand coalition with the Social Democrats. Thüringen looks like it might be an interesting barometer of what might ultimately become the new normal in German politics.

Secondy, and building on this, the Thüringen election takes this to the next level. Given that no party is likely to gain a majority of the seats in the Bundestag on its own, the coalition question thus far has always centered around which pair of parties might work together to form the national government. And, in a worst case scenario—such as is the case now—that would simply be the center-left Social Democrats and the center-right Christian Democrats. The SPD’s abysmal 12.4 percent in Thüringen has ensured that that option simply isn’t possible in Erfurt, and intriguingly, none of the other traditional pairings come even close to working mathematically. Some creative thinking is in order—and it is exactly the same type of creative thinking that politicians in Berlin have long been mulling over.

“Creative” Coalition Solutions: The Afghanistan Option or a Left Alliance

In this case, two three-party alliances were mentioned, and both of them represent real new territory for Germany. On the left of the spectrum the SPD and the Greens are facing up to the fact that they may have to come together and support a government led by the Linke. The Linke is by far the strongest party of the three, and their leader, Bodo Ramelow, is well-placed to become the first ever Linke Ministerpräsident—that despite his party’s links with the GDR’s Socialist Unity Party (SED), the party that governed the GDR unopposed for forty years. Is this the moment when the SPD and the Greens admit in public not just that a three way coalition between the parties is a serious option, but also that the Linke is now so “normal” that they are happy for it to lead it? If so, and it very much looks like this will be the case, German politics really is entering a new er.a—and one where the three parties finally bury the hatchet and admit that they could work together to unseat Angela Merkel’s CDU in the next election in 2017. If such a government were to perform well in Thüringen, then, maybe.

The CDU, on the other hand, had a very weak hand to play even before the election in Thüringen—now it has just lost whatever aces it had previously kept up its sleeve. It will not work with the Linke—and the feeling there is clearly mutual—and it cannot yet work with the AfD. In time, perhaps, but certainly not before the next federal election comes around. That leaves it with the option of persuading both the SPD and the Greens to come on board with it rather than with the Linke in what has already been christened the “Afghanistan Option”—as the colors of the three parties are the same as those on the Afghan flag.

Entertaining though the Afghanistan Option sounds, it is still implausible. And the CDU knows it. The much more likely option is a left-wing anti-CDU alliance. The Linke is now seen as an eminently reasonable, even boring, party and Germans have long got used to the party being a junior party in regional governments. Expect Bodo Ramelow to strike accommodating notes and to negotiate a coalition that brings both parties on board. Predicting how coalitions will behave is in many ways a game for losers; personalities have to work together, party members need to be persuaded to accept difficult compromises. Quite where that can take a coalition is very difficult to predict. But, it is nonetheless worth noting that the “Transnistra Option”—as I think it should be called, given that the flag of the breakaway state has two blocks of red at the top and bottom with a bit of green in the middle—would see parties working together that share largely similar socio-economic visions. There would be challenges, foreign policy rhetoric being one, but if the actors involved want it to work then it will. That won’t have much of an immediate effect on Germany’s everyday politics, but it will certainly send a clear message to the CDU for 2017; Angie, you’re on your own with no real way out.