FelixMittermeier via Pixabay

A Bundestag of Color?

Liza Mügge

University of Amsterdam

Liza Mügge is associate professor in political science and research co-leader of the Diverse Europe group of the Amsterdam Centre for European Studies (ACES) at the University of Amsterdam. During the fall of 2021 she is visiting fellow at the Berlin Institute for Integration and Migration Research (BIM), Humboldt University Berlin, funded by an Alexander von Humboldt Alumni Short Return Visit Grant.

Özgür Özvatan

Humboldt University of Berlin

Özgür Özvatan is a political sociologist, Junior Research Group Leader of the project “’German Islam’ as Alternative to Islamism?” and Co-Director of the Integration and Social Policy Department at the Berlin Institute for Integration and Migration Research, Humboldt University of Berlin. He is Co-Chair of the Immigration Research Network at the Council for European Studies, Columbia University.

An Intersectional Analysis of Diversity in the German Parliament

Equality is the cornerstone of a democracy. Research on gender, sexuality, and ethnicity/race in politics demonstrates that diversity improves the quality of the democratic process and increases political trust and social cohesion.[1] Moreover, diversity, equity, and inclusion in the echelons of political power and decision-making are a matter of social justice. Citizens deserve politicians with whom they can identify or feel at least in some respects connected. Is the new German parliament, the 20th Bundestag, diverse enough? Time to scrutinize the September 2021 elections results.

The newly elected Bundestag is more diverse than its predecessor. The number of women MPs rose from 31 to 34 percent; the number of MPs with a migration background rose from 8 to 11 percent. The outcome of the elections marks a milestone for the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, and queer (LGBTQ) politicians as the first transgender MPs and first MP who identifies as non-binary entered the national political arena. Yet overall, LGBTQ representatives decreased dramatically from 6 (43) to 3 (23) percent.

The categories of women, migration background, and LGBTQ are container labels. None of these groups are homogenous, and categories oftentimes overlap. A woman MP can have a migration background, a citizen with a migration background can be openly LGBTQ, and so on. To address internal group diversity, we conduct a so-called “intersectional” analysis of the incoming cohort of MPs with a migration background.[2] What is the variation in terms of (parental) migration country, gender, and sexuality? Are some parties more inclusive than others? To answer this question, we disentangle party affiliation and the share of incumbents.

Our findings demonstrate that the diversification of the next Bundestag is driven by political parties of the left. Intersectional analysis reveals, among other findings, that there is a higher proportion of MPs with a migration background outside the EU27 and the UK than their colleagues. Moreover, in the non-EU27/UK group, the gender balance is roughly equal. This marks quite a difference with the cohort of MPs with roots in EU27/UK countries, of which only one third are women.

Population Categories and Statistics

According to the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis), 26 percent of the German population had a ‘migration background’ in 2020. Destatis defines citizens with a migrant background as persons who did not, or have at least one parent who did not, acquire German citizenship by birth. If we distinguish between (parental) migration background countries in the EU27/UK on the one hand and the rest of the world on the other, two-thirds (65 percent) have roots in the EU27/UK. The largest groups are German-Turks (13 percent), German-Poles (11 percent), and German-Russians (7 percent). The term migration background is a statistical category and should not be conflated with ethnic or racial identity or belonging.

Roughly half of the overall German population are women (50.5 percent)—that is persons who are ascribed as women by birth. A European study estimated that the percentage of German citizens who identify as LGBTQ was around 7 percent in 2016. Overall, based on their share of the population, citizens with a migration background, women, and LGBT people are underrepresented in the 20th Bundestag.

We are aware that top-down categorizations, particularly those associated with static gender, sexual, and ethnic/racial identities are problematic and even stigmatizing. With this caveat, we apply statistical categories to reveal general trends in inequalities within and between the cohort with a migration background in the Bundestag.

Intersections of Migration Background, Gender, and Sexuality

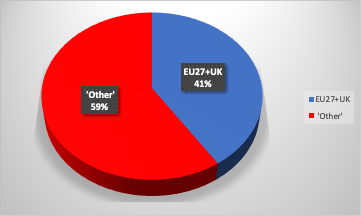

In total, 83 of 735 MPs have a migration background. They have roots in 36 different countries of which 17 are part of the EU27/UK. The remaining 19 countries are located in other regions. The largest group of MPs with a migration background are German-Turks (18), followed by German-Iranians (6), German-Italians (6), and German-Poles (6). Figure 1 shows that almost 60 percent of migration background MPs have a migration background outside the EU27/UK.

Fig. 1. Migration Background MPs

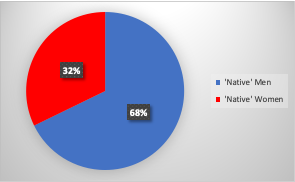

Given that both women and ethnic/racial minorities are underrepresented in politics across the world, one would expect that the percentage of women with a migration background is especially low. The opposite is true. Figure 2 reveals that among migrant background MPs, the gender balance is almost equal (48 percent), while among ‘native’ MPs only about a third (32 percent) are women.

Fig. 2. Comparison of Gender Share across ‘Native’ and Migrant Background MPs

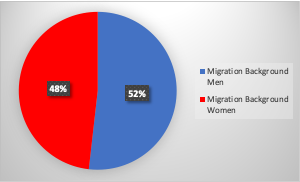

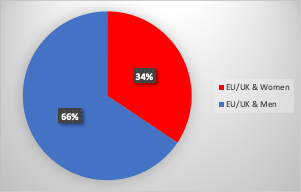

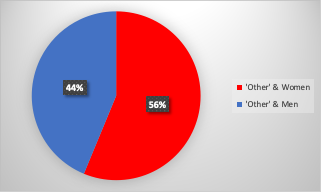

To peel off the next layer, we analyze the gender difference between the two regional groups that we distinguish. Figure 3 shows that among migration background MPs with roots in the EU/UK, around a third are women (34 percent). Among the MPs with roots in other parts of the world, the gender balance is more equal—56 percent of them are women.

Fig. 3. Gender Share of EU27/UK Background and ‘Other’ MPs

Two MPs with a migration background are out LGBTQ: Nyke Slawik (German-Polish, Green Party) and Lars Castelucci (German-Italian, Social Democratic Party). Slawik is one of the two first trans women ever elected to the Bundestag.

Intersections of Political Parties, Gender and Migration Background

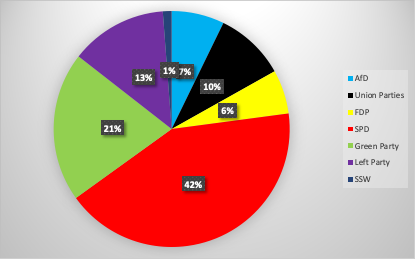

Migration background MPs are predominantly represented in parties of the left. Figure 4 illustrates that the left—the Social Democratic Party (SPD), Green Party, and Left Party—encompasses 76 percent (63 out of 83) of MPs with a migration background. These findings are comparable to patterns in other western European immigration countries where the left has been a catalyst for the diversification of parliamentary politics.[3]

Fig. 4. Share of Migration Background MPs by Political Party

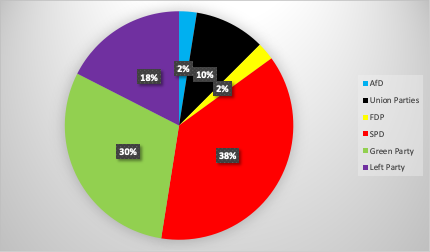

Traditionally, the share of women MPs from leftist parties is higher than from parties on the right. This is especially true for women with a migration background. Figure 5 shows that a large majority (86 percent) of women MPs with a migration background represent parties on the left. The SPD and the Green Party are most inclusive for women with a migration background.

Fig. 5. Share of Migration Background Women MPs by Political Party

Incumbents and Newcomers

Among the migrant background MPs, the share of newcomers (49 percent) is almost equal to incumbents. Additionally, the gender share among newcomers is almost equal, 51 percent are women whereas 49 percent are men. Only 34 percent of the newcomers are from the EU27/UK, whereas 66 percent have their origins elsewhere.

#Weiβwurst: the glass ceiling

The intersectional analysis of MPs with a migration background in the 20th Bundestag shows that this is no homogenous group. We find that particularly women of non-EU27/UK migration background are well represented. Thus, in relative numbers, migrant background women MPs are much better represented than native women MPs. Finally, we see a strong influence of ideology: parties on the left are far more inclusive than parties on the right.

Despite diversification, the Bundestag is not as diverse as it should be. And there is more to critique. Aziz Bozkurt, Federal Chairman of the SPD “Migration and Diversity” working group, tweeted on October 3, 2021, that among all spokespersons of the current coalition talks there are two Michaels but not a single person with a migration history. He added the hashtag #DiversWieWeißwurst—diverse like a Weißwurst (a traditional German white sausage). The lack of diversity baffled left-wing newspapers and political TV shows. This was even more surprising because one of the negotiating parties, the Green Party, has two high profile German-Turkish incumbent members— Cem Özdemir and Ekin Deligöz—who have the experience and authority to take a seat at the table. Migrant background MPs seem to experience a glass ceiling; when it comes to the most powerful positions, they are seldom invited. It is high time for this to change.

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the Mediendiest Integration for helping to establish the migration background of some MPs that were missing from their data.

[1] Robert A. Dahl, On political equality. (Yale University Press, 2008).

Didier Ruedin, Why Aren’t They There? The Political Representation of Women, Ethnic Groups and Issue Positions in Legislatures (Ecpr Press, 2013).

Mala Htun & S. Laurel Weldon, The logics of gender justice: State action on women’s rights around the world (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[2] Liza M. Mügge and Silvia Erzeel, “Double jeopardy or multiple advantage? Intersectionality and political representation,” Parliamentary Affairs 69, no. 3 (2016): 499-511.

[3] Liza M. Mügge, “Intersectionality, recruitment and selection: Ethnic minority candidates in Dutch parties,” Parliamentary Affairs 69, no. 3 (2016): 512-530.